ホーム → 文法 → imabi → imabi beginners 1

With the first installation of IMABI, you will go from zero Japanese to knowing quite a bit about the basics. Content is neatly split up into bite-sized yet accurate depictions of various grammar points that you will absolutely need to foot yourself firmly into the language.

The material found here is presented in a linguistic yet easy to understand approach that does not cut corners while addressing things in a way that is still not overwhelming. You can trust that this section will become easier and easier over time. Remember, it won't hurt to read things over once or twice when you're stumped! Good luck! Or as the Japanese would say, gambatte kudasai!

初級

第2課: Pronunciation II: Consonants

第5課: Kana III: Long Vowels, Double Consonants, & Yotsugana

第6課: Introduction to Kanji 漢字 I

第?課: Introduction to Kanji 漢字 II

第9課: Copular Sentences I: Plain Speech

第10課: Copular Sentences II: Polite Speech

第11課: The Particle Ga が I: The Subject Marker Ga が

第12課: The Particle Wa は I: The Topic/Contrast Marker Wa は

第13課: Adjectives I: 形容詞 Keiyōshi

第14課: Adjectives II: 形容動詞 Keiyōdōshi

第16課: Regular Verbs I: 一段 Ichidan Verbs

第17課: Regular Verbs II: 五段 Godan Verbs

第18課: The Irregular Verbs Suru & Kuru: する & 来る

第20課: The Particle Ka か II: With the Negative

第21課: The Particle Ga が II: The Object Marker Ga が

第23課: Kosoado こそあど I: This & That: Kore/Kono これ・この, Sore/Sono それ・その, & Are/Ano あれ・あの

第24課: Kosoado こそあど II: Here & There: Koko ここ, Soko そこ, & Asoko あそこ

第??課: Yes Phrases: Hai はい, Hā はあ, Ē ええ, & Un うん

第??課: No Phrases: いいえ, いえ, いや, 否, & ううん

第??課: Expressions of Gratitude

第27課: Numbers I: Sino-Japanese Numbers

第28課: Counters I: 円, 冊, 課, 人, 名, 歩, 枚, ページ, 頭, 匹, 足, 台, 階, 歳, & 杯

第34課: The Particle Te: て II: Final Particle

第39課: Countries, Nationalities, & Languages

第42課: Kosoado こそあど III: Kochira こちら, Sochira そちら, & Achira あちら

第44課: The Particle Ka か III: Indirect Question

第49課: Adverbs II: From Adjectives

Japanese is an amazing language that attracts millions of people. Learning how to speak it is no easy task, but the first thing we'll study is how to pronounce it. First off, we will learn about the vowel sounds.

| /a/ | /i/ | /u/ | /e/ | /o/ |

| Katana | Ninja | Sushi | Edamame | Miso |

| Manga | Hibachi | Tanuki | Sake | Koi |

| Tanka | Shiitake | Fugu | Kamikaze | Emoji |

| Karate | Yakitori | Shabu-shabu | Ikebana | Udon |

| Wasabi | Sashimi | Kombu | Zen | Soba |

| V | CV | C |

| A (ah) | Ka (mosquito) | Ka.n (can) |

| I (stomach) | Ni (two) | Ki.n (gold) |

| U (cormorant) | Su (vinegar) | U.n (good fortune) |

| E (picture) | Me (eye) | Me.n (noodles) |

| O (tail) | Ko (child) | To.n (ton) |

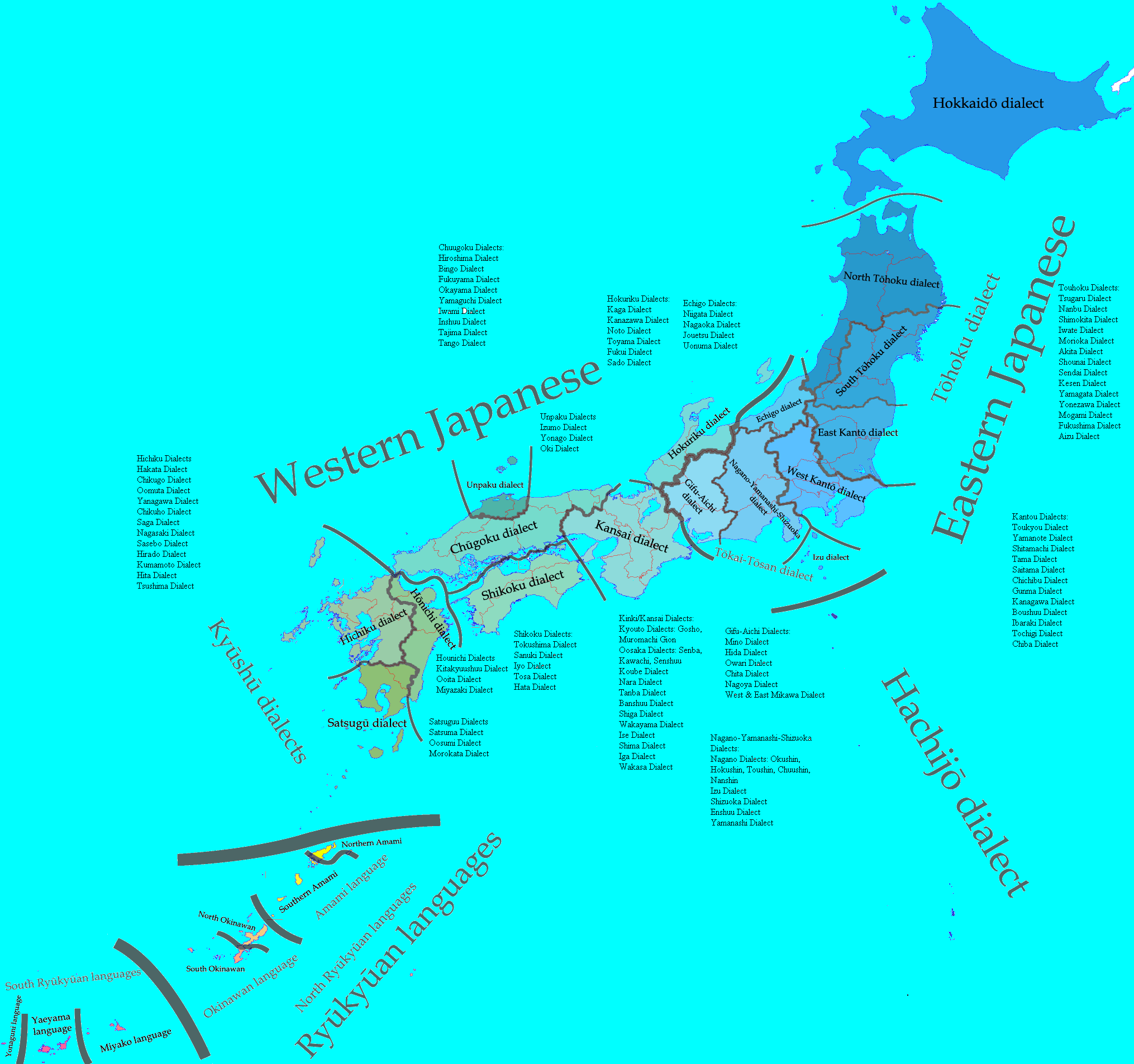

In Standard Japanese--the form of the language any Japanese speaker will understand and the form that you are beginning to learn--there is what is called a pitch accent system. Every mora of a phrase is assigned a pitch. This assigned pitch may either be high or low. In a full sentence, you will hear pitch go up and down as phrases are strung together.

Stress in English

Proper pitch in Japanese is not necessary for pronunciation. In theory, you could still be understood even if you were to mess up the pitch of every mora. Having correct pitch, however, will make your speech sound more native-like, and in turn, easier to understand.

In English, syllables acoustically have both pitch alternation and different degrees of emphasis in enunciation, which is known as stress. This is in contrast with Japanese which only has pitch alternation, causing Japanese to sound monotone to the English ear. Theoretically, it is similarly the case in English that a speaker could be understood even if the stress of every word were placed on the wrong syllable.

This is not to say that stress allocation never changes the meaning of words in English. In fact, there are some rather systematic ways in which this is true. As examples of this, below are three words that differ in part of speech as well as subsequently in meaning due to the placement of pitch. In the left-hand column, the words are understood as nouns due to stress being placed on the first syllable. In the right-hand column, the words are understood as verbs due to stress being placed on the second syllable.

| 1st-Syllable Stress | Meaning | 2nd-Syllable Stress | Meaning |

| ADD-ict | A person who is addicted to a particular substance. | add-ICT | To cause to become dependent. |

| OB-ject | A thing. | ob-JECT | To state disagreement. |

| RE-cord | To make a record. | re-CORD | To set down. |

Despite many such words existing in English, it would be wrong to claim that pronouncing the majority of words with the wrong accent would result in a different word or non-word. For instance, if you were to pronounce the word "English" with the stress on the second syllable instead of on the first syllable, any native speaker should still be able to recognize the word and understand you.

Just as is the case with various English accents, pitch accent will differ based on where a person is from. So, although it's important to understand the basic framework of pitch in Japanese, and although you will be exposed to the pitch contours of many phrases as you progress through this curriculum, don't let this hamper your studies if the minute details of pronunciation become overwhelming.

Pitch Accent in Standard Japanese

In Standard Japanese, there are four kinds of pitch contours that a phrase can have. Regardless of how short or long a phrase is, the pitch contour will always be one of the four patterns with no exceptions. This predictability will allow you to quickly pick up on how Japanese should sound, and in turn, it may help you more quickly acquire the system as a whole.

Think of an entire sentence as being a pitch roller coaster. Every mora isn't an individual ride with its own loops and turns. Rather, a mora is only one loop of the ride--nothing more. You must put the loops (morae) together so that the segments (phrases) of the ride come together to make a complete ride. Lastly, the loops that make up the ride only come in 4 varieties.

In the chart below, each of the four pitch patterns are laid out. In the far-right column, you will find an example word for each pattern. All four examples happen to be homophonous (sound the same), only differing in pitch. This is to demonstrate that, though not a widespread phenomenon, phrases are still occasionally distinguished with pitch accent.

"L" and "H" stand for "low-pitch mora" and "high-pitch mora", both standing for one mora each. This means that H-L stands for two morae, H-L-L stands for three morae, etc. As a reminder of this, a mora-count is placed after each such contour notation.

Sometimes, a single word is not the only component to a phrase. Most phrases are made with one word along with an add-on that attaches to it, and it is the resultant combination that is treated as a "phrase." This is important to understand because pitch allocation is done at the phrasal level, NOT the individual word level. As such, "L" and "H" are seen in parentheses to indicate what the pitch accent of a phrase would continue to be if it were made longer.

| 1 | Pitch is high for the first mora, drops on the second mora, and stays low for any remaining morae that follow. Ex. H(-L) ①, H-L(-L) ②, H-L-L(-L) ③, H-L-L-L(-L) ④ |

hashì (chopsticks) |

| 2 | Pitch starts low on the first mora, peaks at high pitch on the middle mora(e), drops back to low pitch for any following morae of the word. Ex. L-H-L ③, L-H-H-L ④ |

hanasu (to speak) |

| 3 | Pitch starts low on the first mora, peaks at high pitch on the last mora, and then drops to low pitch on any morae that follow the word. Ex. L-H-(L) ②, L-H-H(-L) ③ |

hashi↓ (bridge) |

| 4 | Pitch starts low on the first mora, becomes high pitch on the second mora, and then the pitch stays high even once the word is over unto anything that follows. Ex. L(-H) ①, L-H(-H) ②, L-H-H(-H) ③, L-H-H-H(-H) ④ |

hashi (edge) |

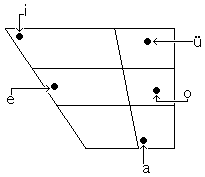

As mentioned earlier, there are only five vowels in Japanese: /a/, /i/, /u/, /e/, and /o/. Below you will see how the five vowels of Japanese are roughly pronounced. The vowels are pronounced clearly and sharply like the American English approximates provided. However, it cannot be stressed enough that these are approximates.

| A | Like the "a" sound in the word "buy." | Ta↓ (field) |

| I | Like the "i" in "police." | Ki↓ (tree) |

| U | Like the "oo" in "mood." Compress your lips without protruding them. | Uta↓ (song) |

| E | Like the "e" in "set." | Ike↓ (pond) |

| O | Like the "o" in "oh." | Oka (hill) |

Although the chart says that /u/ is like the "oo" in the word "mood," this isn't quite accurate. In fact, there is no form of English that has the /u/ found in Standard Japanese. However, by compressing your lips rather than protruding them forward, the resulting /u/ will be something like the one in Japanese.

Although the other vowels are almost identical to the ones found in American English, the Japanese /a/ actually only shows up in diphthongs in American English. A diphthong is when two vowels blend together to form a complex vowel sound. You start off pronouncing one vowel sound, but at the end it sounds like something else. For example, the vowel sound in the word "height" is an example of a diphthong, and the onset of this word is exactly how the Japanese /a/ is pronounced.

Juxtaposed Vowels

In English, complex vowel sounds called diphthongs are created by beginning a vowel sound with one quality but ending it with another. For instance, in the word "kite," the vowel starts out as "a" but ends as "i." The opposite of a diphthong is a monophthong, which is a vowel whose quality doesn't change during its pronunciation. This is what all vowels in Japanese are thought to intrinsically be.

In Japanese, diphthongs are said not to exist because of how the moraic structure of the language dictates how sounds are organized. Instead of treating a word like hai (yes) as one syllable, you treat it as two morae: /ha/ + /i/.

Acoustically, juxtaposed vowels do slightly blend together. However, native speakers still conceptualize them as two separate entities. This is because pitch can fall or rise without needing an intervening consonant. Even in words just composed of vowels, pitch contours cannot be ignored, as is demonstrated below.

| Love/indigo |

Ai | To meet | Au | Ue↓ |

Starvation |

| Fish |

Uo | Blue | Ao | Ue | Above |

| Nephew | Oi | Hey! | Oi | Iu | To say |

Exception Note: The word iu is pronounced as /yuu/. Exceptions like this, though, are few and far between in Japanese.

In Japanese, short vowels are distinguished from long vowels. A short vowel is a vowel utterance equal to one mora in length. If a vowel is elongated to take up two morae, it becomes a long vowel. Pitch can consequently rise or drop inside long vowels because they're treated as two morae.

Consequently, vowel length contrasts thousands and thousands of words. Mistakes at the beginning are inevitable, but recognizing distinctions like this now will spare you a lot of potential heartache.

| Short /a/ | Obasan (aunt) | Long /a/ | Obaasan (grandma) |

| Short /i/ | Ie↓ (house) | Long /i/ | Iie (no) |

| Short /u/ | Yuki↓ (snow) |

Long /u/ | Yuuki (courage) |

| Short /e/ | E↓ (painting) | Long /e/ | Ee (yes) |

| Short /o/ | To (door) | Long /o/ | Too (ten things) |

Pronunciation Note: Do not pronounce "oo" as a long /u/ sound. This is incorrect!

False Long Vowels

What makes a long vowel truly a long vowel and not just the same vowel next to each other is there being nothing that obstructs the pronunciation of the vowel as it spans two morae. In both English and Japanese, the pronunciations of vowels begin with glottal stops. Whenever you say the phrase "uh-oh", you should feel an audible release of air after completely stopping airflow from the glottis (Adam's apple) at the start of "uh" and "oh."

In Japanese, long vowels are always contained in a single element of a word. If one element of a word only ends in the same vowel as the first sound in the following part of the word, the vowel of that second element will begin with a glottal stop like any other word-initial vowel sound. This glottal stop insertion also helps determine the pitch of the phrase.

Transcription Note: In the words below, to show where elements of a word begin and end, periods will be inserted to indicate these boundaries.

| Scene | Shiin | Consonant/Cause of death | Shi.in |

Trivia Note: Vowels are called boin in Japanese.

The Pronunciation of "Ei": [ei] or [ē]

In Japanese, the vowel combination "ei" is usually pronounced as a long /e/ (ē). All such words come from Chinese roots. Because this sound change is technically optional, you don't have to worry so much about whether to pronounce an "ei" as [ei] or [ē]. After all, we haven't even learned about what exactly words made from Chinese roots look like. For this lesson, alternative pronunciations of a word are listed for you.

Transcription Notes:

1. Long /e/ are written as "ee" so that pitch contours can be designated. However, do not be confused by this spelling and pronounce "ee" as a long "i" sound.

2. To show where elements of a word begin and end, periods will be inserted to indicate these boundaries. "Ei" can only be pronounced as [ē] if it's within the same element of a word, so these boundaries are very important.

3. If a word is not derived from Chinese roots, /ei/ is always pronounced as [ei].

| Plan | Kei.kaku Kee.kaku |

Student | Sei.to See.to |

Stingray | Ei |

| English | Ei.go Ee.go |

Native | Neitibu | Cellphone | Kei.tai Kee.tai |

| Management | Keiei Kee.ee |

Clock | To.kei | Correct answer | Sei.kai See.kai |

| Proclamation | Sei.mei See.mee |

Process | Kei.ro Kee.ro |

Hair color | Ke.iro |

The Pronunciation of "Ou": [ou] or [ō]?

In Japanese, the vowel combination "ou" is usually pronounced as a long /o/ (ō). Most such words come from Chinese roots, but this is not always the case. This sound change, unlike the one above, is not optional for the words it affects.

Knowing which words are and aren't affected by this sound change is a luxury that comes about from knowing a lot about word origins. For this lesson and the next, any word in which a word that would be spelled as "ou" but is instead pronounced as a long /o/ will be spelled as "oo." This means if you do see "ou," you should pronounce it literally as such. Try not to read "oo" as a long "u" sound because this is incorrect.

Transcription Note: To show where elements of a word begin and end, periods will be inserted to indicate these boundaries.

| Already | Moo | King | Oo | Method | Hoo.hoo |

| To think | Omo.u | Large | Ookii | Calf | Ko.ushi |

| Action | Koo.doo | Robbery | Goo.too | Sauce | Soosu |

The majority of words in Japanese are made by combining consonants and vowels. What was not discussed was how the consonants of Japanese sound and differ with those found in English.

Just as there are consonants in English that don't exist in Japanese, there are also consonants in Japanese that don't exist in English. Furthermore, the consonants that Japanese shares with English need not be pronounced exactly the same. In fact, it's safe to assume that all consonants are slightly different in their own unique ways.

To fully grasp how consonants are pronounced, some technical terminology will need to be learned. However, just as was the case in the previous lesson, such terminology will always be accompanied with an explanation on its initial use.

Transcription Note: Japanese words introduced in this lesson will be written in Romaji (English letters). Additionally, morae with high pitch will be put in bold, and subsequent pitch drops will be marked with ↓. To understand why these conventions are used, refer back to Lesson 1.

In Lesson 1, we briefly learned that a consonant is a speech sound that involves obstructing airflow from the lungs in some way. Japanese has fewer consonants than English, but this doesn't mean the ones it has are all easy to acquire and pronounce for English speakers. First, we need to learn what constitutes a consonant. How do we know something is a distinct consonant and not just a variation of the same thing? Because these distinctions aren't the same across languages, we'll need to understand the answers to these questions to know how to pronounce Japanese properly.

What is a Phoneme?

Two sounds are considered contrastive if interchanging the two can cause a change in meaning. If two sounds can contrast each other, they are treated as phonemes of the language.

To demonstrate what this looks like in English, consider the consonants /b/ and /p/. These consonants are distinct phonemes of English. This can be proven by numerous minimal pairs in which the difference between /b/ and /p/ is the only factor that tells the words apart.

| /b/ | /p/ |

| Bit | Pit |

| Ban | Pan |

| Tab | Tap |

As demonstrated by the words above, a minimal pair is simply two (or more) words that differ only by a single sound in the same position that have different meanings.

What is an Allophone?

In both English and Japanese, there are phonetically (acoustically) different sounds that are treated as the same phoneme. For instance, consider the pronunciation of the consonant /t/ in English. Have you ever noticed that the "t" in "top" and the "t" in "stop" are not pronounced the same? If you're a native speaker of English and pronounce "top" with a hand in front of your mouth, you'll feel a puff of air hit your hand. This is called aspiration. If you pronounce "stop" likewise, you shouldn't feel that puff of air hit your hand. This means that English has both an aspirated and non-aspirated version of /t/, and both are treated as the same sound. These different versions of a single phoneme are called allophones.

| Aspirated /t/ | Non-Aspirated /t/ |

| Team | Steam |

| Toll | Stole |

| Tray | Stray |

This distinction between aspirated and non-aspirated /t/ does not change the meaning of a word in English. Although they are in complementary distribution with each other--allophones that don't occur in the same location in a word--a speaker could theoretically replace one for the other and be understood. It is because they cannot appear in the same location of a word that makes it impossible for them to contrast words with each other.

There are also instances in both English and Japanese where the same consonant could be pronounced differently in the same location of a word without changing the meaning. This is called free variation. Think of the word "data." Some people pronounce the first "a" like the "a" in "cat" whereas others pronounce it like the "a" in "date." Neither group is wrong. It's just that the pronunciation of the vowel is in free variation between those two pronunciations.

Phoneme vs. Allophone is Language Specific

What counts as a phoneme or allophones of the same phoneme differs from language to language. It is also possible for a sound to be treated as an allophone of another in one environment but be treated as a separate phoneme in other environments, all within the same language. Although knowing this may seem trivial, the reason for why you should understand what these terms are is because of the fact that languages are all not the same in how they treat sounds. If you are a native speaker of language(s) other than English, you will have different yet just as problematic difficulties in distinguishing certain Japanese sounds if in fact they aren't differentiated in your own language(s).

Transcription Note: Just as in Lesson 1, phonemes will be placed in // whereas allophones will be placed in [].

The Phonemes of Japanese

At the phonemic level, Japanese can be said to have at least 16 distinct consonant phonemes depending on how one likes to divvy things up.

| /k/ | /g/ | /s/ | /sh/ | /t/ | /ch/ | /n/ | /h/ |

| /f/ | /b/ | /p/ | /m/ | /r/ | /y/ | /w/ | /N/ |

The chart above shows all the distinct phonemes of Japanese. However, it is important to understand now that these are not all the possible sounds of Japanese because some of them have allophones and some of them happen to be allophones of other phonemes listed in the chart.

For the rest of this lesson, we'll learn exactly how to pronounce each of these consonants based on intrinsic features to their pronunciation. Because Japanese pronunciation isn't complicated aside from having features that may not be shared in the languages you speak, there should be no worries about having to memorize tons of variant pronunciations.

Most consonants come in pairs. For instance, /k/ and /g/ are both made in the exact same place in the mouth. The only difference is that pronouncing /g/ causes the vocal folds of the mouth to vibrate whereas /k/ does not. Consonants that do not cause the vocal folds to vibrate are called unvoiced consonants, and consonants that do cause the vocal folds to vibrate are called voiced consonants. Voicing is a seen across many languages to make such consonant pairs like /k/ and /g/.

Examples of unvoiced consonants in English include /k/, /s/, /t/, /h/, and /p/. These consonants alone are seen in thousands of words. Although English has more unvoiced consonants, these are the basic ones it shares with Japanese.

| /k/ | /s/ | /t/ | /h/ | /p/ |

| Kite | Seek | Tea | Hat | Pie |

| Key | Sit | Take | Heat | Peak |

| Case | Say | Toe | Host | Pay |

In English, unvoiced consonants are typically pronounced with aspiration. In Japanese, unvoiced consonants tend to be slightly more aspirated than they are in languages like Spanish but not nearly as so as in English or Korean.

The Unvoiced Consonants of Japanese

The basic unvoiced consonants of Japanese, as mentioned above, are /k/, /s/, /t/, /h/, and /p/. Overall, these consonants are less aspirated than their English counterparts. Other differences exist, of course, which is why each consonant will be introduced individually.

Pronouncing /k/

Just as is the case in English, /k/ is made by placing the back of the tongue against the soft palate in the back of the mouth.

| Kuki↓ | Kaki | Oyster | Keika | Progress |

Pronouncing /t/

/t/ is made by placing the blade of the tongue behind the upper teeth. When the vowel /u/ follows /t/, it becomes [ts]. This is an example of an allophone. An allophone is a variation of the same consonant in the confines of a particular language. This [ts] is the same as the /ts/ consonant cluster found in words like "its" in English. Unlike English, you must never drop the "t" in [ts] in Japanese. This means that "tsunami" is pronounced as /tsu.na.mi/.

Additionally, /t/ becomes [ch] when followed by the vowel /i/. However, the [ch] in Japanese is not like the "ch" in "chair." The Japanese [ch] is produced by first stopping air flow and then placing the blade of the tongue right behind the gum line while the middle of the tongue touches the hard palate of the mouth.

| Take | Bamboo | Tochi | Land | Tsuki↓ | Moon |

Pronouncing /s/

The consonant /s/ is pronounced just like it is in English, but it becomes [sh] when followed by /i/. When pronouncing [sh], the middle of the tongue is bowed and raised towards the hard palate of the mouth. Note that [sh] is made not as farther back in the mouth as is the case in English.

| Isu | Chair | Keisatsu | Police | Shiitsu | (Bed) sheet(s) |

Pronouncing /h/ & /p/

/p/ is known as a plosive sound. It is made by releasing air upon opening one's lips. In Japanese, it isn't all that common because most words with /p/ come from other languages.

Both /p/ and /h/ are pronounced the same as in English, but /h/ has two allophones. When followed by /i/, /h/ sounds most like the "h" in "hue." When followed by /u/, it becomes [f]. The Japanese [f], though, is created by bringing the lips together and blowing air through them without using the teeth.

| Hako | Box | Hifu | Skin | Futsuu | Ordinary | Penki | Paint |

More Example Words

| Asa | Morning | Te↓ | Hand(s) | Koko | Here | Sake | Alcohol |

| Ashi↓ | Foot/leg | Shiai | Match/game | Pasupooto | Passport | Sake | Salmon |

| Katsu | To win | Tsuaa | Tour | Aka | Red | Pai | Pie/pi |

| Ka↑ | Mosquito | Suutsu | Suit | Soto | Outside | Tsuchi↓ | Dirt/earth |

| Ase | Sweat | Satoo | Sugar | Tako | Octopus/kite | Chika | Underground |

| Kako | Past | Heishi | Soldier | Hoshi | Star | Kutsu↓ | Shoes |

| Hi↓ | Fire/day | Kotatsu | Kotatsu | Tsukau | To use | Kasa | Umbrella |

Vowel Devoicing

When the vowels /i/ and /u/ are in between and/or after unvoiced consonants--/k/, /t/, /s/, /h/, and /p/ along with their respective allophones--they often become devoiced (silent). Devoicing is a very distinctive feature of Standard Japanese pronunciation.

As an example, the phrase for "good morning" sounds like "o-ha-yo-o go-za-i-ma-s". However, it is important to note that many speakers, especially those that don't come from East Japan, do not devoice vowels.

Devoicing is never required in a word. In fact, even when a vowel could be devoiced, it doesn't mean it will. There's significant speaker variation. One thing that is certain, however, is that devoicing should not under normal circumstances occur between and/or after voiced consonants.

Practice: Pronounce the words below with the underlined vowels devoiced.

Kushami (Sneeze)Tafu (Tough)Hito(↓) (Person)

The unvoiced consonants and their allophones mentioned above all have a voiced consonant counterpart. For every voiced consonant, its pronunciation is the same as its unvoiced counterpart minus voicing.

| Unvoiced Counterpart | Voiced Counterpart |

| /k/ | /g/ |

| /s/ | /z/~[dz] |

| /sh/ | /j/ |

| /t/ | /d/ |

| [ts] | [dz] |

| [ch] | [dj] |

| /h/ (and allophones) | /b/ |

| /p/ | /b/ |

There are a few peculiarities that need to be discussed. However, before going into too much detail, /j/ and /dj/ will be mentioned later in this lesson.

1. /z/ typically becomes [dz] at the start of words. /dz/ tends to become [z] inside words, but this isn't always so. /z/ sounds like the "z" in "zoo," whereas /dz/ sounds like the "ds" in "kids." However, it is important to note that many speakers cannot tell the difference between the two sounds.

2. /h/, its allophones, and /p/ correspond with /b/. /b/ is made by bringing the lips together and then releasing them. This means its articulation is the same as /p/ but not as /h/.

3. /g/ can be pronounced as /ng/ inside words. This pronunciation is particularly common in the north and east of Japan.

Try pronouncing the following example words.

| Sokudo | Speed | Baka | Idiot | Zutsuu | Headache |

| Tsu(d)zuki | Continuance | Kaze | Wind | Deeto | A date |

| Kazu | Number | Kage | Shadow | Gitaa | Guitar |

| Bataa | Butter | Toge↓ | Thorn | Doku↓ | Poison |

More Voiced Consonants

There are also voiced consonants that do not have unvoiced counterparts. These sounds are listed in the chart below.

| [n] | Made with the blade of the tongue on the back of the upper teeth with /a/, /e/, and /o/, behind the ridge of the mouth with /i/ (like in news), and behind the teeth with /u/ (like in noon). |

| [m] | Pronounced by bringing the two lips together just as in English. |

| [r] | Its pronunciation varies drastically. It is typically pronounced as a flap, which is only seen in American English as the "t" in many words such as "water." At the beginning of a word, it sounds almost like /d/. Sometimes it's pronounced as a trill or like /l/. |

| [y] | Pronounced the same in English by bringing the tongue up to the hard palate. This means it is a palatal consonant. |

| [w] | Its pronunciation is very similar to the Japanese /u/. Rather than protruding your lips, you compress them. It is only used with the vowels /a/ and /o/, but its use with /o/ won't even become important until later on in your studies. |

The differences in pronunciation detailed above make Japanese sound significantly different from English. Many sounds tend to be closer to the teeth, which is the case for [n] and [r], and movement of the tongue and parts of the mouth are more limited in range. To practice pronouncing these consonants, try saying the following words out loud.

| Fune | Boat | Neko | Cat | Mune↓ | Chest |

| Yowai | Weak | Yakusoku | Promise | Kawa↓ | River |

| Mura↓ | Village | Umi | Sea | Tana | Shelf |

| Kami | God | Kami | Hair/paper | Yubi↓ | Finger |

| Wana | Trap | Karada | Body | Rei | Example/zero |

Palatal consonants are made by the body of the tongue touching against the hard palate of the mouth. In Japanese, these consonants are usually limited to the vowels /a/, /u/, and /o/, and they're all created with the help of the consonant /y/. First, we'll look at those palatal consonants shown below in the chart.

| Consonant | C + /a/ | C + /u/ | C + /o/ |

| /y/ | /ya/ | /yu/ | /yo/ |

| /ky/ | /kya/ | /kyu/ | /kyo/ |

| /gy/ | /gya/ | /gyu/ | /gyo/ |

| /ny/ | /nya/ | /nyu/ | /nyo/ |

| /hy/ | /hya/ | /hyu/ | /hyo/ |

| /py/ | /pya/ | /pyu/ | /pyo/ |

| /by/ | /bya/ | /byu/ | /byo/ |

| /my/ | /mya/ | /myu/ | /myo/ |

| /ry/ | /rya/ | /ryu/ | /ryo/ |

Terminology Note: Palatal consonants are all semi-voiced due to the use of /y/ following the initial consonant. The voicing of the initial consonant doesn't change. Thus, /gy/ would be fully voiced whereas /ky/ would not be voiced initially but become voiced by the end of the consonant. Here, /y/ acts more like a semi-vowel more so than another consonant, which is why none of these palatal consonants are treated as consonant clusters. Instead, they can be viewed as more additional phonemes in the language.

Usage Note: In loan-words, these consonants may be used with other vowels.

Most of these combination are very common in Japanese. They are most frequently found in words that come from Chinese. Below are some examples.

| Hyoo | Vote | Kyaku | Customer | Kyuu | Nine |

| Myoo | Weird | Hyaku↓ | 100 | Kyoo | Today |

| Myaku | Pulse | Ryuu | Dragon | Byooki | Illness |

| Gyaku | Reverse | Ryoo | Quantity | Ryaku | Abbreviation |

Other Palatal Consonants

The remaining palatal sounds that have yet to be looked at are /sh/, /ch/ and /(d)j/.

As we learned earlier, [sh] and [ch] are allophones of /s/ and /t/ respectively. They can also be treated as separate phonemes. This is because all five vowels can follow them, allowing them to become contrastive.

The voiced counterpart for both /sh/ and /ch/ is /(d)j/. This phoneme /(d)j/ has two allophones: [dj] and [j]. The former sounds like the j-sound in "judge," and the latter sounds like the j-sound in "seizure." Many speakers pronounce this phoneme as [dj] whenever it appears at the start of a word or after another consonant but as [j] anywhere else. Others only use the [dj] pronunciation.

| Shuu | Week | Kaisha | Company | Ocha | Tea |

| Choosa | Investigation | Chero | Cello | Shefu | Chef |

| Shooko | Proof | Shima↓ | Island | Jiko | Accident |

| Kaji | Housework/fire | Jookyoo | Situation | Jukyoo | Confucianism |

Consonants may be lengthened in Japanese just like vowels. When you make a long consonant, the sound is perceived as sounding harder. The length of time you use to pronounce it increases from one mora to somewhere in between one and two morae. However, speakers conceptualize long consonants as being two morae.

The consonants that are typically doubled in Japanese are non-voiced consonants. These consonants include /p/, /k/, /t/, /s/, /sh/, /ch/, and /ts/. As far as transcribing them is concerned, they will be written as /pp/, /kk, /tt/, /ss/, /ssh/, /tch/, and /tts/ respectively.

| Shippai | Failure | Matchi | A match | Yokka | Four days | Zasshi | Magazine |

| Happa | Leaf/leaves | Kokka | Nation | Shuppatsu | Departure | Hassoo | Conception |

| Kassooro | Runway | Satchi | Inferring | Sakka | Author | Sakkaa | Soccer |

Usage Note: Voiced consonants are only voiced in a handful of loanwords from other languages, but even then they're usually pronounced as their long unvoiced counterparts.

There is a special voiced consonant in Japanese called the "moraic nasal." It counts as a mora on its own. Although usually transcribed as an "n," its pronunciation varies depending on the environment.

In its basic understanding, it is what's called a uvular "n" that is best transcribed as /N/. The uvula is back in the mouth, but when you pronounce it, the mouth constricts as if you were producing a regular /n/, which makes it sound more like the /n/ you're used to hearing but not quite.

This sound has a lot of allophones because it assimilates (becomes more similar) with the sound that follows. Because things can get quite complicated, we'll go over each situation separately with plenty of examples along the way. In Standard Japanese, this sound can't start words, but it is still quite complicated.

When /N/ is before a /p/, /b/, or /m/, it becomes [m]. This means that /m/ can in fact be a doubled with the aid of /N/.

| Sampo | A walk | Shimpai | Worry | Kampeki | Perfect |

| Bimboo | Destitute | Kambu | Executive | Sembei | Rice cracker |

| Sammyaku | Mountain range | Tammatsu | Device | Chimmi | Delicacy |

| Sontoku | Loss and gain | Sentaku | Choice/laundry | Kantoo | The Kanto Region |

| Kondate | Menu | Shindai | Bed | Kandoo | Impression |

| Minna↓ | Everyone | Tennai | Inside store | Tennoo | Emperor |

| Shinrai | Faith | Kanri | Management | Shinri | Mentality |

| Shinka | Evolution | Kankaku | Feeling | Sanka | Participation |

| Kingyo | Gold fish | Kango | Sino-Japanese word | Kangae | Idea |

| Shinchuu | Brass | Tanchiki | Detector | Sanchoo | Summit |

| Kanja | Patient | Tanjoobi | Birthday | Shinjuku | Shinjuku |

Transcription Note: Typically, /dj/ is spelled as "j" since /j/ is largely pronounced as [dj].

When before vowels, /y/, /w/, /s/, /sh/, /z/, /h/, and /f/, /N/ sounds like a nasal vowel from the back of the mouth. At any rate, the vowel before /N/ is always nasalized, but when /N/ is followed by a vowel, all you may hear is a really nasal vowel and then the following vowel. Typically, this /N/ is usually just a very nasal ũ. Although this is usually spelled as "n" for simplicity, it'll be spelled as "ũ" below.

| Taũ'i | Unit | Koũwaku | Perplexity | Deũsha | Train |

| Kaũzei | Tariff | Kiũyuu | Finance | Kaũsai | The Kansai Region |

Pronunciation Notes:

1. When before /z/, some speakers pronounced /N/ as [n].

2. /Deũsha/ may also be pronounced as [deũsha].

At the end of words, /N/'s default pronunciation is [N]. However, there are plenty of speakers that pronounce it like a nasal vowel as seen above in this position. In singing, it will even be pronounced as [m]. This is actually true for any instance of /N/ in singing. For the purpose of this section, [N] will be written below as "N."

| NihoN | Japan | KaN | Can | HoN | Book |

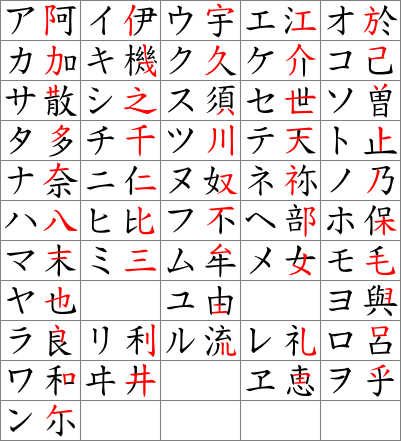

Japanese is written with a mixed script composed of several parts. Of these are two systems called Kana. These systems spell words moraically. These means that, unlike an alphabet, every symbol will stand for a mora. Thus, a symbol may stand either for a "consonant + vowel" (CV), a "vowel" (V), or a "consonant" (C).

The two Kana systems are called Hiragana and Katakana. Because there are many symbols and rules to learn per system, we will first study Hiragana. Then, in Lesson 3 we'll learn the symbols of Katakana. After we've covered both sets, we'll learn about Kanji, which are Chinese characters used in Japanese writing.

Curriculum Note: Just as has been the case for the past two lessons, pitch notes will be provided for the vocabulary used. High pitch is designated as text in bold. Pitch falls are noted with a ↓.

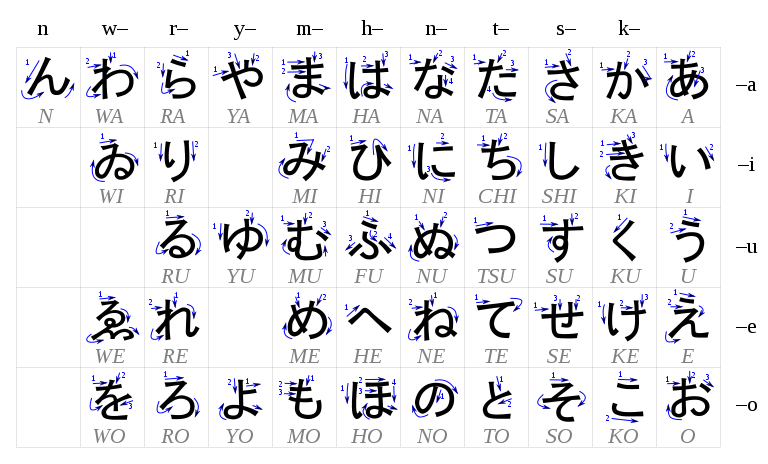

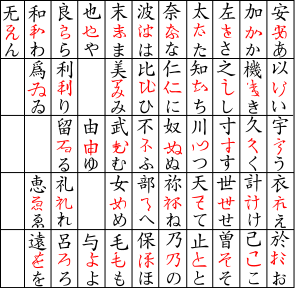

Kana represent the morae of Japanese. As we learned in Lesson 1, a mora is an equal time unit of speech. Kana can be organized into a chart called the Gojūonzu, which means the table of 50 sounds. Although it doesn't actually have 50 sounds in it, they are deemed to be the most basic sound combinations in Japanese, which are called seion.

Each Kana system has its own set of symbols. That means once you have mastered the Hiragana symbols below, you'll have to prepare yourself to learn an entirely different set for the same sound combinations. As tedious as this might seem, the two systems are used differently. The most important and most used system is Hiragana, which is why it is being introduced to you first.

HIRAGANA

The basic symbols of Hiragana, as stated above, are organized into a chart called the Gojūonzu. This chart is shown below with each basic symbol. Notice how the chart is organized. Stoke orders are listed, and all the allophones of sounds we learned in the previous lesson are shown in their respective columns.

Curriculum Note: Print this sheet out and have it at hand as we continue onward.

Usage Notes:

Of these characters, all except the symbols for we and wi are actually used. These two characters live on only in names, place names, and old literature. Because there is the chance you will encounter them, when you do see them, read them as "e" and "i" respectively as the "w" has dropped from their actual pronunciations. This is largely why the symbols are no longer seen today.

Similarly, the symbol for wo is usually pronounced by "o" by most speakers. However, the traditional pronunciation "wo" is still heard depending on personal preference, dialect, as well as occasion. For instance, in music, singers tend to be conservative in pronunciation. This is also the case when people slow down their speech to purposefully enunciate every sound clearly.

Of these characters, all but the symbols for we, wi, wo, and n can start words. Also, the symbol for wo is only used in names or as a grammatical word that cannot stand alone, which we will learn about later.

Handwriting Notes:

1. Write strokes from top to bottom and left to right.

2. Make sure the end of the second stroke in あ is crossing the curve of the final stroke.

3. Make sure that the final stroke in け is slightly farther down than the first.

4. For せ, the second stroke usually doesn't have a hook.

5. For い, こ, た, ふ, り, and ゆ, don't connect the strokes together.

6. For む, if you connect stroke 2 and 3, do not add another slash.

7. Make sure the stroke 3 for お is not positioned far away from the rest of the character.

8. In more proper handwriting, the last stroke in さ and き is not connected with the rest.

Examples

The best way to see if you can read Hiragana is to practice with actual words. Below is a list of 30 common words written without any aids.

| Shape | かたち | Dream | ゆめ↓ | Japan | にほん |

| Usual | ふつう | End | おわり | Promise | やくそく |

| Snow | ゆき↓ | Kitten | こねこ | Proof | あかし |

| Chair | いす | Bowl | うつわ | Plate | さら |

| Payment | しはらい | Seat | せき | Speculation | すいそく |

| Gymnasium | たいいくかん | Strength | ちから↓ | Pathway | つうろ |

| Store clerk | てんいん | Chicken meat | とりにく | Accent | なまり↓ |

| Duty | にんむ | Bypath | ぬけみち | Drink | のみもの |

| Secret | ひみつ | Star | ほし | Command | めいれい |

| Night | よる | Young person | わかもの | Bus/train line | ろせん |

Diacritics: ゛ & ゜

There are two diacritics that can be added to symbols that change the consonant of the symbol in question. These diacritics are the ゛ (dakuten/nigori↓) and the ゜ (handakuten). The first diacritic changes a consonant into a voiced consonant. A voiced consonant causes the vocal folds to vibrate. The second diacritic changes /h/ to a /p/.

When writing these characters, you write the diacritics last. It's important to note how there are two characters for /ji/ and /zu/. These symbols are not always pronounced exactly the same, but we will go into greater detail about this later.

Examples

The hardest part to mastering the diacritics will simply be remembering to use them and realizing that the pronunciation of a symbol will change because of them. For practice, below are 30 common words that utilize them.

| Number | かず | College student | だいがくせい | Key | かぎ↓ |

| Walk | さんぽ | Mountain climbing | とざん | Culture | ぶんか |

| Throat | のど | Poison | どく↓ | Yes and no | さんぴ |

| Cheers | かんぱい | Nosebleed | はなぢ | Attachment | てんぷ |

| Electricity | でんき | Potentiality | そこぢから | Hippopotamus | かば |

| Skin | はだ | Furniture | かぐ | Wall | かべ |

| Elbow | ひじ↓ | Part | ぶぶん | Whirlpool | うず |

| Continuation | つづき | Scale | きぼ | Wind | かぜ |

| Eyelash | まつげ | Crevice | ひびわれ | Tatami room | ざしき↓ |

| Mirror | かがみ↓ | Family | かぞく | Map | ちず |

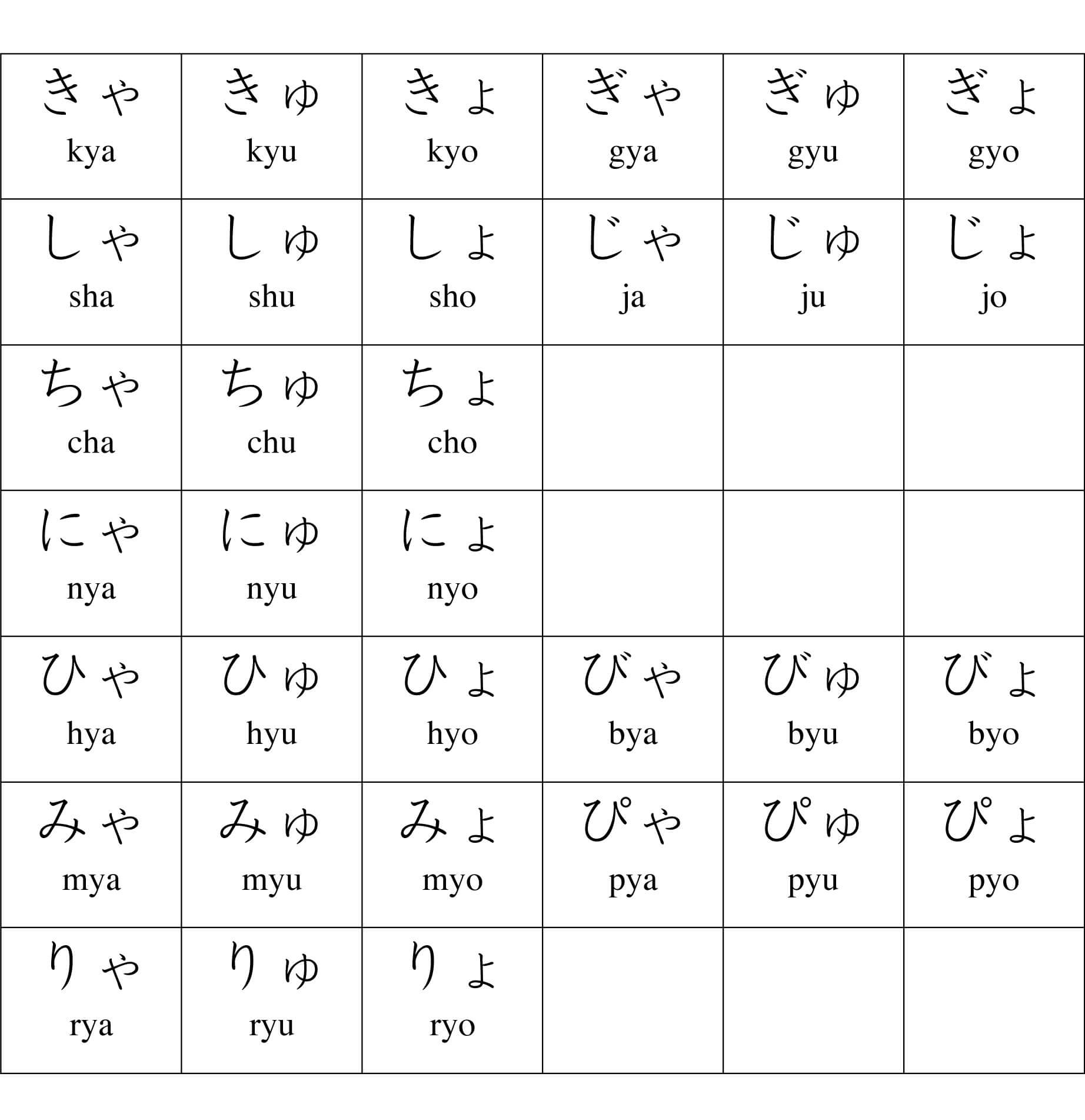

Palatal Sounds

Palatal sounds are created by placing the tongue on the hard palate of the mouth. Many consonants in Japanese can be palatalized and then followed by the vowels /a/, /i/, /u/, and /o/. In the case of /i/, palatalization is an inherent part of the pronunciation of the sound combination. For instance, /ki/, /shi/, /chi/, /ni/, /mi/, /hi/, and /ri/ are all technically palatalized. This is simply part of the natural process of pronouncing them.

The way Japanese creates more sound combinations with palatalized combinations is by having /ya/, /yu/ and /yo/ follow a consonant. When this happens, new consonants are produced. In Hiragana, these combinations are created by using an i-sound symbol with a shrunken y-sound symbol--ゃ, ゅ, or ょ.

Similarly to above, there are two ways to write /ja/, /ju/, and /jo/. For now, we'll put aside how they differ in pronunciation and usage and solely focus on memorizing these glyphs. Note, though, that you will rarely see the variants that utilize ぢ.

Pronunciation-wise, the ry-sounds will be the most difficult to master as the Japanese /r/ tends to be difficult as it is for native English speakers to acquire.

Examples

Below are 30 words utilizing these glyphs to help you learn them.

| Resident | じゅうみん | Parking Injection |

ちゅうしゃ | Giant | きょじん |

| Meow-meow | にゃんにゃん | Acronym | りゃくご | Tune |

きょく |

| Seafood | ぎょかいるい | Inn | りょかん | Opposite | ぎゃく |

| 600 | ろっぴゃく↓ | Tathagata | にょらい | Studying abroad | りゅうがく |

| Cow milk | ぎゅうにゅう | Bathing | にゅうよく | Customer | きゃく |

| Concentration | しゅうちゅうりょく | Processing | しょり | Society | しゃかい |

| Touch down | ちゃくりく | Tea | おちゃ | Directly | ちょくせつ |

| Weak point | じゃくてん | Tutor | じょしゅ | Pulse | みゃく↓ |

| Teacup | ゆのみぢゃわん | Hyuga | ひゅうが | 100 | ひゃく↓ |

| Chinese | ちゅうごくご | Properly | ちゃんと | Address | じゅうしょ |

| i-sound + や・ゆ・よ | i-sound + ゃ・ゅ・ょ |

| じゆう (Freedom) | じゅう (Ten/gun) |

| りゆう (Reason) | りゅう (Dragon) |

| きゆう (Needless anxiety) | きゅう (Nine) |

| しゆう (Private ownership) | しゅう (Week/state) |

To Continue

So far, we have covered the unique glyphs that compose Hiragana. What we have not learned is how long consonants and vowels are transcribed. We have also not learned about what situations Hiragana is even used in. Both of these topics require that we first go over Katakana as comparing the two is essentially in understanding these topics properly.

Practice

Part I: Change the following words into Hiragana.

1. Kemuri (smoke)

2. Amagumo (rain cloud)

3. Uta↓ (song)

4. Sekai (world)

5. Karate(karate)

Part II: Change the following words in Hiragana into Rōmaji.

1. かのじょ (She) 2. しょだな (Bookshelf)

3. にほんご (Japanese language) 4. さかな (Fish)

5. にんげん (Human) 6. だいがく (College)

7. ひと (Person) 8. あした↓ (Tomorrow)

In the previous lesson, we learned about how Japanese is a mixed script. The previous lesson was all about learning the individual symbols of Hiragana. In this lesson, our goal will be to learn all the individual symbols for Katakana.

Hiragana and Katakana both represent the same sound combinations (morae). As such, there won't be any differences in pronunciation between an /a/ written in Hiragana and one written in Hiragana. However, the two scripts are used in different circumstances. Their rules for other aspects of spelling such as long vowel notation are also not exactly the same. For now, we will focus solely on learning the individual symbols of Katakana. As you will soon see, there are more symbols to learn in Katakana than there is for Hiragana. This means you have plenty of work ahead of you in this lesson.

Of the two Kana systems, Katakana is the least used. However, that doesn't mean it isn't used, and it doesn't mean that it isn't important to learn. One cannot properly read Japanese without knowing both systems. The two systems are still used in different ways. The way they're used also affects how complex the systems are. Katakana, as you will see, has an additional set of combinations not used in Hiragana. This means it'll take a little more effort to memorize Katakana than Hiragana. With that being said, let's begin.

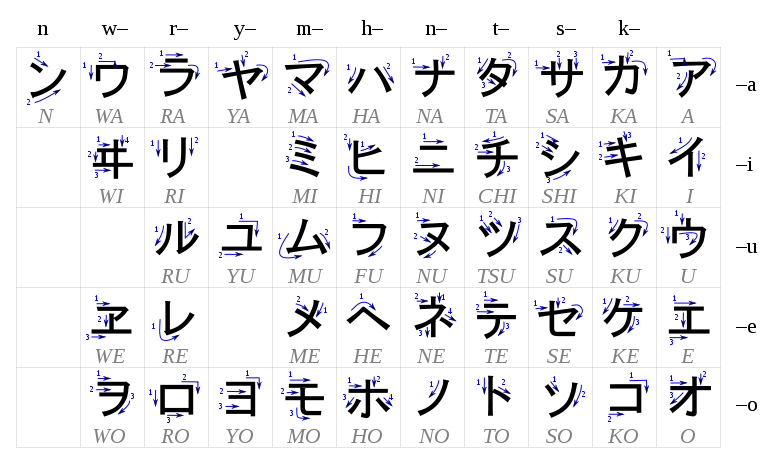

KATAKANA

The basic symbols of Katakana, just as was the case with Hiragana, are organized into a chart called the Gojūonzu. This chart is shown below with each basic symbol. Just like for Hiragana, notice how the stoke orders are listed and how all the allophones of sounds we've learned about are shown in their respective columns.

Curriculum Note: Print this sheet out and have it on hand as we continue onward.

Usage Notes:

Of these characters, all of them except the symbols for we and wi are typically used. These two characters live on only in names, place names, and old literature. Because there is the chance you will encounter them, when you do see them, read them as "e" and "i" respectively as the "w" has dropped from their actual pronunciations. This is largely why the symbols are no longer seen today.

Similarly, the symbol for wo is usually pronounced by "o" by most speakers. However, the traditional pronunciation "wo" is still heard depending on personal preference, dialect, as well as occasion. For instance, in music, singers tend to be conservative in pronunciation. This is also the case when people slow down their speech to purposefully enunciate every sound clearly. Unlike in Hiragana, the Katakana symbol for wo is hardly used at all. This means you won't get many opportunities to see it actually used.

Of these characters, all but the symbols for we, wi, wo, and n can start words. The symbols for we and wi are deemed obsolete. Also, the symbol for wo is only used in names or as a grammatical word that cannot stand alone, which we will learn about later.

Handwriting Notes:

1. Write strokes from top to bottom and left to right.

2. Horizontal strokes come before vertical strokes.

3. Take especial note to the stroke orders of シ and ツ. For シ, its third stroke is irregularly written from the bottom upward, which is how you can distinguish it from ツ, which is written regularly.

4. Also take note of the stroke orders of ソ and ン. For ン, its second stroke is irregularly written from the bottom upward, which is how you can distinguish it from ソ, which is written regularly.

5. When there are horizontal strokes that span the length of the symbol, those strokes aren't first from top to bottom regardless if other strokes may start higher up. Take キ as an example.

Examples

As your first chance at reading practice, below are 60 common words that are spelled in Katakana. Although it's not necessary that you memorize them all now, you'll find that many of them are words you're already very familiar with.

| Access | アクセス | Assistant | アシスタント | ASEAN | アセアン |

| Africa | アフリカ | America | アメリカ | Aluminum | アルミ |

| Good-looking guy | イケメン | Italy | イタリア | Earbud | イヤホン |

| Air conditioning | エアコン | Eroticism | エロ | Oceania | オセアニア |

| Offline | オフライン | Cocktail | カクテル | Custom | カスタム |

| Sponge cake | カステラ | Camera | カメラ | Karaoke | カラオケ |

| Calcium | カルシウム | Mouse | マウス | Christ | キリスト |

| Classmate | クラスメイト | Christmas | クリスマス | Koala | コアラ |

| Coin | コイン | Siren | サイレン | Santa | サンタ |

| System | システム | Scenario | シナリオ | Restaurant | レストラン |

| Hormone | ホルモン | Synchronize | シンクロ | Stress | ストレス |

| Centi(meter) | センチ | Seoul | ソウル | Solo | ソロ |

| Towel | タオル | Tennis | テニス | Toilet | トイレ |

| Hotel | ホテル | Minus | マイナス | Nylon | ナイロン |

| Tomato | トマト | Ton | トン | Knife | ナイフ |

| Necktie | ネクタイ | Quota | ノルマ | Handkerchief | ハンカチ |

| Stapler | ホチキス | Marathon | マラソン | Milk | ミルク |

| Mexico | メキシコ | Moscow | モスクワ | UNESCO | ユネスコ |

| Toyota | トヨタ | Link | リンク | Lemon | レモン |

| Russia | ロシア | Request | リクエスト | Wine | ワイン |

Diacritics: ゛ & ゜

The diacritics we learned about last lesson are used in exactly the same way in Katakana. These diacritics, the These diacritics are the ゛ (dakuten/nigori↓) and the ゜ (handakuten), represent voiced consonants and the consonant /p/ respectively.

Just as was the case with Hiragana, you write the basic symbol before adding the diacritics. Additionally, there are two characters for /ji/ and /zu/. However, their pronunciations/usage aren't 100% the same. For now, focus on memorizing these symbols.

Examples

Below are 60 common words that utilize these diacritics. Although it is not necessary that you memorize them all, they are all common words that bring purpose to using Katakana as the majority of these words are solely written in Katakana.

| Advice | アドバイス | Radio | ラジオ | England | イギリス |

| Pokemon | ポケモン | Event | イベント | India | インド |

| Ego | エゴ | Egypt | エジプト | Apron | エプロン |

| Holland | オランダ | Casino | カジノ | Gas | ガス |

| Capsule | カプセル | Gift | ギフト | Jellyfish | クラゲ |

| Mongolia | モンゴル | Golf | ゴルフ | Convenience store | コンビニ |

| Size | サイズ | Sandals | サンダル | Running | ランニング |

| Swimming | スイミング | Pants | ズボン | Celebrity | セレブ |

| Zombie | ゾンビ | Diamond | ダイヤモンド | Taipei | タイペイ |

| Dance | ダンス | Design | デザイン | Digital camera | デジカメ |

| TV | テレビ | Germany | ドイツ | Door | ドア |

| Dollar | ドル | Napkin | ナプキン | Trash | ゴミ↓ |

| Knob | ノブ | Hiking | ハイキング | Basketball | バスケ |

| PC | パソコン | Bus | バス | Pachinko | パチンコ |

| Bread | パン | Banana | バナナ | Panda | パンダ |

| Piano | ピアノ | Visa | ビザ | Pizza | ピザ |

| Vitamin | ビタミン | Video | ビデオ | Building | ビル |

| Pink | ピンク | Judea | ユダヤ | Frying pan | フライパン |

| Browser | ブラウザ | Blog | ブログ | Veranda | ベランダ |

| McDonald's | マクドナルド | Medal | メダル | Memo | メモ |

Palatal Sounds

Remember that palatal sounds are created by placing the tongue on the hard palate of the mouth. Consonants are naturally palatalized in Japanese when followed by /i/ or /y/. For those created with /y/, shrunken y-sound symbols must be paired with a full-sized i-sound symbol. In Katakana, these combinations are as follows.

Just as was the case with above with there are being two ways to write the says, /ji/ and /zu/, the same can be said for /ja/, /ju/, and /jo/. The variants that use ヂ are essentially obsolete as far as spelling actual, common words is concerned.

Examples

Not all these characters are used as frequently as others. Although some are extremely common, some are only found in certain kinds of words. Others are hard to find without being used with long vowels and consonants. Since we haven't learned what those rules are for the two Kana systems, the 30 examples words are limited to words with short consonants and vowels that are actually common expressions.

| Casual | カジュアル | Curriculum | カリキュラム | Cabbage | キャベツ |

| Cancel | キャンセル | Gambling | ギャンブル | Shirt | シャツ |

| Chandelier | シャンデリア | Jump | ジャンプ | Jogging | ジョギング |

| Mandarin dress | チャイナドレス | Chime | チャイム | Channel | チャンネル |

| Pajamas | パジャマ | Condominium | マンション | Pure | ピュア |

| Jazz | ジャズ | Munich | ミュンヘン | Genre | ジャンル |

| Gang | ギャング | Goggling | ギョロギョロ | Hopping | ピョンピョン |

| Junior | ジュニア | Meow-meow | ニャンニャン | Nuance | ニュアンス |

| Awkwardness | ギクシャク | Wriggling | ニョロニョロ | Pyeongyang | ピョンヤン |

| Chocolate | チョコ | Tunisia | チュニジア | Champion | チャンピオン |

Additional Katakana

Unlike Hiragana, Katakana is used to transcribe far more sound combinations. Although we have not learned exactly when either system is used and why, you may have noticed that a lot of the example words in this lesson have been for loan-words from other languages. This is one purpose of Katakana that is heavily reflected in the inventory of sound combinations as an effect.

The most frequently used extensions are those for the consonants /sh/, /j/, /t/, /d/, /ch/, /f/, and /w/. As you can see, all these additional combinations involve using a shrunken symbol next to a full-sized one.

| Y | W | V | S | SH | J | T | D | CH | TS | F | KW | GW | |

| A | ヴァ | ツァ | ファ | クァ クヮ |

グァ グヮ |

||||||||

| I | ウィ | ヴィ | スィ | ズィ | ティ | ディ | ツィ | フィ | |||||

| U | ヴ | トゥ | ドゥ | ||||||||||

| E | イェ | ウェ | ヴェ | シェ | ジェ | チェ | ツェ | フェ | |||||

| O | ウォ | ヴォ | ツォ | フォ | |||||||||

| Y | テュ | デュ |

Pronunciation Notes:

1. The v-sounds are overwhelmingly pronounced as b-sounds by most speakers.

2. Additional w-sounds and y-sounds are usually pronounced broken up as if they were written with full-sized characters. For instance, kiwi can either be pronounced as kiui キウイ or kiwi キウィ.

Examples

The combinations shown above are essentially all additional combinations that are of any significant importance in writing practical words that are actually used by Japanese speakers. However, they aren't all equal in frequency. With that being said, it isn't possible to show practical examples of each combination at this point without having to delve into information beyond the reach of this lesson. Nevertheless, the 30 words will provide you plenty of practice.

| Korean won | ウォン | Ending | エンディング | Figurine | フィギュア |

| The web | ウェブ | Chef | シェフ | Disc | ディスク |

| Native | ネイティブ | Negative | ネガティブ | Fight(ing spirit) | ファイト |

| File | ファイル | Family restaurant | ファミレス | Film | フィルム |

| Philippines | フィリピン | Manifesto | マニフェスト | Czech | チェコ |

| Share | シェア | Pretzel | プレッツェル | Cafe | カフェ |

| Highway | ハイウェイ | Fan | ファン | Chess | チェス |

| Violin | ヴァイオリン | Fake | フェイク | Yes | イェス |

| Font | フォント | Wedding dress | ウェディングドレス | Wink | ウィンク |

| Wikipedia | ウィキペディア | Shakespeare | シェイクスピア | Fondue | フォンデュ |

Word Notes:

1. "Violin" is typically spelled as バイオリン.

2. イェス is not the typical means of saying "yes"; it is always used in an English-based context.

To Continue

In the next lesson, we will learn about how to write long vowels and consonants in both Hiragana and Katakana. We will also learn about what the differences are between the variant ways to write the sounds /ji/, /zu/, /ja/, /ju/, and /jo/. After which point, we'll learn about what Kanji and then move on to learning how Kana and Kanji are used together to write properly in Japanese.

Practice

Part I: Spell the following words in Katakana.

1. Piano(Piano)

2. Tesuto (Test)

3. Wirusu/Uirusu (Virus)

4. Kariforunia (California)

Part II: Romanize the following words.

1. スリル (Thrill)

2. シネマ (Cinema)

3. マスコミ (The media)

4. キャビン (Cabin)

5. パリ (Paris)

Every language has an orthography for its script(s). In any orthography, there are rules that govern how the writing system(s) are used. For the most part, Japanese orthography in regard to Kana is rather straightforward, but there are a few special cases.

In Hiragana, long vowels are typically written by doubling the vowel. As you can see below, only long /e/ or /o/ sounds are extra complicated. The reason why these two long vowels are two possible spellings is because of all the words that have been borrowed from Chinese. Sometimes, spelling doesn't always match pronunciation. As readers of English, you should know this oh too well.

| Long /a/ | Long /i/ | Long /u/ | Long /e/ | Long /o/ |

| ああ | いい | うう | ええ えい |

おお おう |

The next thing to do is see actual words with each of these long vowels. The information we learned about long /e/ and long /o/ sounds in Lesson 1 will be extremely relevant in this lesson.

Long /a/, /i/, & /u/

To create long vowels for /a/, /i/, and /u/, all you do is double the vowel symbol. In the word charts below, the first column shows their spellings in Hiragana. Because word type is a major factor later on in this lesson, the word type for all words shown in this section are also provided. There are three main sources of vocabulary in Japanese: native (words that are indigenous to Japanese), Sino-Japanese, and loan-words. Sino-Japanese words are words that were either borrowed or created with roots from Chinese. These words are alternatively referred to as Kango (the Japanese terminology for Sino-Japanese) in the charts below. Loan-words are borrowings from modern world languages that have managed to find their way into Japanese. In the third column.

Transcription Note:

1. Because pitch contours will be marked on the Hiragana spellings, long vowels will be romanized with macrons in the charts below except for long /i/, which will be written as "ii."

2. High pitch and pitch drops will be denoted the same way as previous lessons, just with their Hiragana spellings.

Curriculum Note: False long vowels, vowels that happened to be juxtaposed next to each other but are in fact belong to separate word elements, are not represented as examples of long vowels in the charts below.

| Long /a/ | Word Type | Meaning |

| Ā ああ |

Native | Ah |

| Okāsan おかあさん |

Native | (Someone's) mother |

| Obasan おばさん |

Native | Aunt; middle-aged woman |

| Obāsan おばあさん |

Native | Grandmother/old woman |

Usage Note: Long /a/ is not a common long vowel. In Hiragana, long /a/ is limited to native words.

| Long /i/ | Word Type | Meaning |

| Ojisan おじさん |

Native | Uncle/middle-aged man |

| Ojiisan おじいさん |

Native | Grandfather/old man |

Usage Note: Long /i/ is also not a common long vowel. In Hiragana, long /i/ is limited to native words.

| Long /u/ | Word Type | Meaning |

| Sūgaku すうがく |

Kango | Math |

| Fūfu ふうふ |

Kango | Married couple |

| Gyūniku ぎゅうにく |

Kango | Beef |

Long /e/: ええ vs えい

Whereas long /e/ in native words is always spelled with ええ, it is spelled as えい in Sino-Japanese, in which case it may alternatively be literally pronounced as [ei]. This literal pronunciation is preferred in many regions of Japan as well as in conversation pronunciation, especially in singing. Note that all other instances of えい outside Sino-Japanese vocabulary must be pronounced as [ei].

| [ē] | Word Type | Meaning |

| Onēsan おねえさん |

Native | Older sister/young lady/miss |

| Hē へえ |

Native | Really? |

| [ē] or [ei] | Word Type | Meaning |

| Ēga/Eiga えいが |

Kango | Movie |

| Mēshi/Meishi めいし | Kango | Business card |

| [ei] | Word Type | Meaning |

| Mei めい | Native | Niece |

| Hei へい | Native | Wall/fence |

| Ei えい |

Native | Stingray |

Long /o/: おお vs おう

Long /o/ is usually spelled in native words as おお. Historically, the second "o" would have originally been ほ or を, depending on the word. In Sino-Japanese words, long /o/ is written as おう. When おう is used in native words, it either stands for a long /o/ or "o.u." Typically, おう in native words is always a long /o/ except when it is at the end of a verb. The ending of a verb is treated as a separate element, thus breaking apart what otherwise would be a long vowel.

| [ō] |

Word Type | Meaning |

| Kōri こおり |

Native | Ice |

| Tōi とおい |

Native | Far away |

| Ōkii おおきい |

Native | Big |

| Ōi おおい |

Native | Many |

| Mō もう |

Native | Already |

| Otōsan おとうさん |

Native | (Someone's) father |

| Kanjō かんじょう | Kango | Emotion |

| Gakkō がっこう |

Kango | School |

| Nōgyō のうぎょう | Kango | Agriculture |

| [ou] | Word Type | Meaning |

| Ou おう | Native | To chase |

| Ōu おおう |

Native | To cover |

For Katakana, long vowels are typically represented with a mark that looks similar to a hyphen: ー. It's normally either called a chō’ompu ちょうおんぷ or bōbiki ぼうびき. As Katakana is used primarily to write foreign words, you are primarily going to use and see this with foreign words.

| Word | Meaning | Word | Meaning |

| Tēburu テーブル | Table | Aisukuriimu アイスクリーム | Ice cream |

| Intāchenji インターチェン ジ | Interchange | Mēru メール | |

| Fināre フィナーレ | Finale | Kōchi コーチ | Coach |

| Sōda ソーダ | Soda | Kompyūtā コンピューター | Computer |

| Aisutii アイスティー | Ice tea | Sēru セール | Sale |

| Orenjijūsu オレンジジュース | Orange juice | Chiizu チーズ | Cheese |

| Daunrōdo ダウンロード | Download | Kōhii コーヒー | Coffee |

| Intabyū インタビュー | Interview | Sūtsukēsu スーツケース | Suitcase |

Curriculum Note: A lot can be said about how to transcribe and pronounce loan-words. For now, know that long vowels are typically written with ー in Katakana.

In both Hiragana and Katakana, double consonants are created by preceding a symbol with a shrunken tsu. In Hiragana, this is っ. In Katakana, this is ッ. As we have learned previously, unvoiced consonants are typically the only consonants doubled. However, /n/ and /m/ can technically be long, but the symbol for N will be what precedes the main symbol (ん in Hiragana and ン in Katakana).

| Word | Meaning | Word | Meaning |

| Chotto ちょっと |

A little | Matto マット |

Mat |

| Hokkē ホッケー |

Hockey | Shippai しっぱい |

Failure |

| Jetto ジェット |

Jet |

Intānetto インターネット |

Internet |

| Sakkā サッカー |

Soccer | Robotto ロボット |

Robot |

With Katakana, voiced consonants are only voiced in certain loan-words or in exaggerated pronunciations. Even in such expressions, these doubled voiced consonants are still usually pronounced as if they were unvoiced so long as there is an unvoiced equivalent. For instance, "bed" is beddo but is normally pronounced as betto. Nonetheless, it remains spelled as ベッド. Consonants for which this all applies include: g, z, d, h, f, b, r, w and y.

| Word | Meaning | Word | Meaning |

| Baggu バッグ |

Bag | Beddo ベッド | Bed |

| Suggoi すっごい |

Cool! | Reddo Sokkkusu レッドソックス | The Red Socks |

| Aipaddo アイパッド |

iPad | Bagudaddo バグダッド | Baghdad |

| Hottodoggu ホットドッグ |

Hot dog | Bahha バッハ | Bach |

Glottal Stops

In Lesson 1, we learned about what glottal stops were. A glottal stop is made by forcibly stopping air in one's Adam's apple. When an expression ends in a glottal stop, a small tsu is used to indicate this pronunciation. An example of this is itah いたっ (ouch!).

Yotsugana refer to Kana that spell what were traditionally four distinct consonants: /z/, /dz/, /j/, and /dj/. Pronunciation-wise, /z/ is usually pronounced as /dz/ and can only be pronounced as /z/ inside words. As for /j/ and /dj/, the two sounds are overwhelmingly both pronounced as [dj]. Previously, we learned when these consonants are used, but we haven't gone over the rules for how to write them correctly in Kana.

Below are the symbols in question in both Hiragana and Katakana. In the chart, symbols are listed as "common", "uncommon" or "rare."

| Sound | Hiragana | Rarity | Katakana | Rarity |

| JI | じ | Common | ジ | Common |

| ZU | ず | Common | ズ | Common |

| DZU | づ | Uncommon | ヅ | Rare |

| DJI | ぢ | Uncommon | ヂ | Rare |

| JA | じゃ | Common | ジャ | Common |

| JU | じゅ | Common | ジュ | Common |

| JO | じょ | Common | ジョ | Common |

| DJA | ぢゃ | Uncommon | ヂャ | Rare |

| DJU | ぢゅ | Rare | ヂュ | Rare |

| DJO | ぢょ | Rare | ヂョ | Rare |

Because Katakana is used largely for loan-word transcriptions, which is why symbols traditionally associated with the consonants /dj/ and /dz/ are all rare. Typically, the symbols traditionally associated with the consonants /z/ and /j/ are used regardless of how the consonant is pronounced. The only times when づ・ヅ and ぢ・ヂ are used is when they are immediately preceded by つ・ツ and ち・チ respectively, or when they are the voiced forms of つ・ツ and ち・チ respectively in compound expressions.

| Nosebleed | Hana(d)ji はなぢ |

Instruction | Shiji しじ |

| Shrinkage | Chi(d)jimi ちぢみ |

Bell | Suzu すず |

| Continuation | Tsu(d)zuki つづき |

Monopoly | Hitorijime ひとりじめ |

| Class | Jugyō じゅぎょう | Jaguar | Jaga ジャガー |

| Monotone | Ippon(d)jōshi いっぽんぢょうし | Information | Jōhō じょうほう |

| Suggestion/hint | Ire(d)jie いれぢえ | Crescent Moon | Mika(d)zuki みかづき |

| Within reach | Te(d)jika てぢか | To spell | Tsu(d)zuru つづる |

| Proximity | Ma(d)jika まぢか | Hairpiece | Zura ヅラ |

Word Note: ヅラ is an abbreviation of katsura かつら (hairpiece), and it is usually spelled in Katakana largely to emphasize its existence as an abbreviation.

Curriculum Note: To learn more, see Lesson 355.

Japanese, as we have learned, is written with a mix of different writing systems put together. In Lessons 3-5, we learned about the Kana writing systems: Hiragana ひらがな and Katakana カタカナ. These systems alone, though, do not comprise all the characters that are used to write Japanese. Japanese is also written with characters called Kanji 漢字. These are symbols which originated from China that were then adapted to write the Japanese language.

Unlike with Kana, it will be impossible to learn every Kanji all in one go. This is because over 3,000 individual characters are commonly used. The use of Kanji is undoubtedly the hardest aspect to writing Japanese, but it is also the most rewarding.

In this lesson, we will learn about how Kanji are constructed. By doing so, you’ll be able to get an idea of how they are formed and written down. In the next lesson, we’ll learn about how Kanji are read as their pronunciations are varied and must be learned on a case-by-case basis. Because this is an introductory lesson with no actual vocabulary given, you do not have to memorize any of the Kanji provided as examples.

Kanji are completely different from ひらがな and カタカナ. Whereas these systems look like foreign alphabets, the same cannot be said for Kanji. In fact, Kanji don’t even correspond to specific sounds like the letters of an alphabet or syllabary would. Instead, Kanji represent actual units of meaning, and to accomplish this, they are composed of one or more building blocks. These building blocks are known as radicals.

All Kanji in existence are composed of one or more 214 distinct radicals.

廴 |

阝 | 扌 | 忄 | 犭 | 冫 | 亅 |

| Long Stride | Village | Hand | Heart | Beast | Ice | Barb |

These are just five examples of some of the most common radicals. Radicals will always have one (or more interrelated) meaning(s) assigned to them, allowing the reader to make an accurate educate guess as to what the Kanji they’re in mean. This means that if you see, for example, 忄 in a Kanji, it has a good chance of having a meaning related to emotion.

Many radicals happen to be independent Kanji themselves. After all, they each possess some core meaning. Not all radicals can be used this way, but this is due to historical happenstance.

山 |

土 |

木 |

火 |

糸 |

Mountain |

Earth |

Tree |

Fire |

Thread |

These radicals also happen to be used as independent Kanji with the same meanings. Just like the previous radicals, when you see them in other Kanji, their meanings are incorporated into said resultant Kanji. To demonstrate this, below are five Kanji using the radical for “fire.”

災 |

炎 |

燃 |

煙 |

灰 |

Disaster |

Flame |

Burn |

Smoke |

Ash |

As demonstrated by these examples, the same radical can appear slightly differently depending on where it is in a Kanji, but the meaning the radical adds to the character doesn’t change.

On the topic of shape, radicals come in seven types based on how they fit in Kanji. These types also help determine how characters are written—the stroke order. Radicals can fit into more than one type as there is some give and take involved when combining radicals together.

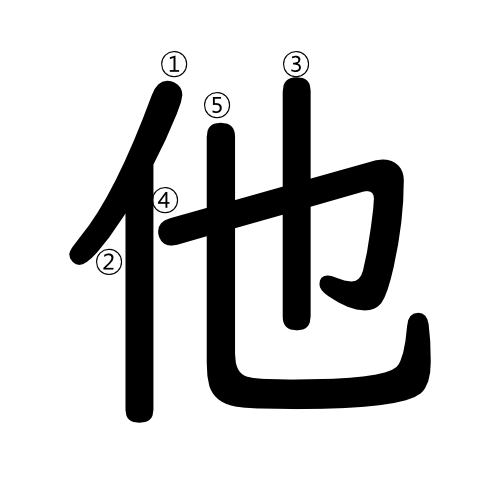

The first category of radicals establishes the general rule that strokes of Kanji are generally written from left to right. These radicals, naturally, are found on the left-side of a Kanji. Let’s look at the radical 亻 meaning “person.” When you see it to the left of a character, you know that the Kanji has something to do with people.

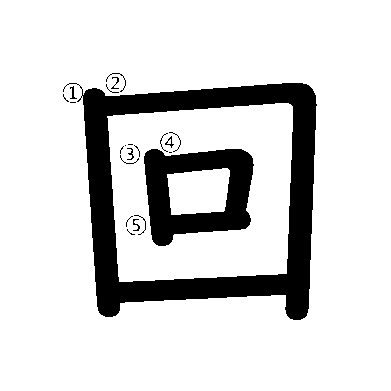

To demonstrate how these radicals are written, consider the character 他 meaning “other(s).”

To demonstrate how the radical 亻 contributes meaning-wise to Kanji, consider the following characters.

体 |

伴 |

仲 |

仏 |

休 |

Body |

Companion |

Relation |

Buddha |

Rest |

Terminology Note: These radicals are also known as へん radicals in Japanese.

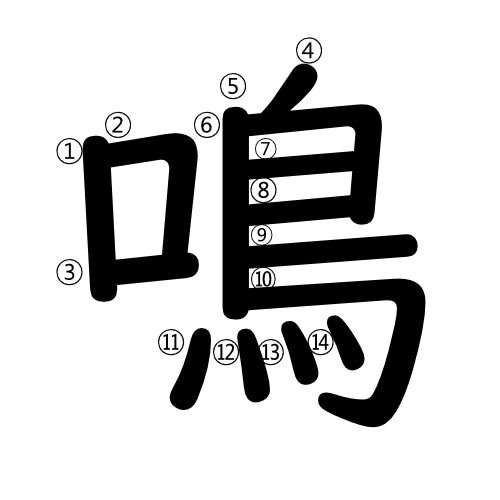

The second category of radicals follow the rule of strokes being written left to right, meaning that these radicals are written last. Let’s look at the radical 鳥 meaning “bird.” When you see it to the right of a character, you know that the Kanji has something to do with birds.

To demonstrate how these radicals are written, consider the character 鳴 meaning “chirp/cry.”

To demonstrate how the radical 鳥 contributes meaning-wise to Kanji, consider the following characters.

鴨 |

鳩 |

鶴 |

鶏 |

鴎 |

Duck |

Dove |

Stork |

Chicken |

Seagull |

Terminology Note: These radicals are known as つくり radicals in Japanese.

The third category of radicals establishes the general rule that strokes of Kanji are generally written from top to bottom. Let’s look at the radical 艹 meaning “grass”. When you see it in the upper-half of a character, you know that the Kanji has something to do with plant life.

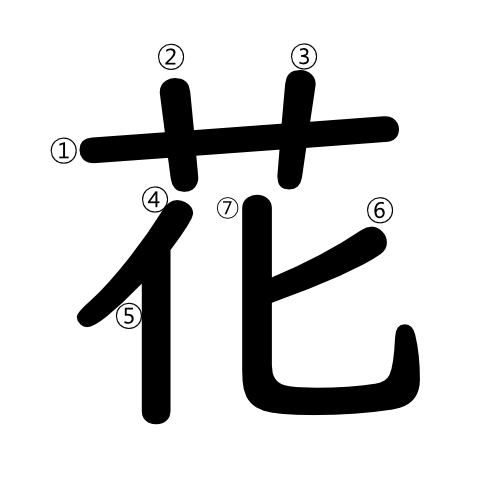

To demonstrate how these radicals are written, consider the character 花 meaning “flower.”

To demonstrate how the radical 艹 contributes meaning-wise to Kanji, consider the following characters.

芋 |

茶 |

苗 |

苺 |

芽 |

Potato |

Tea |

Seedling |

Strawberry |

Sprout |

Terminology Note: These radicals are known as かんむり in Japanese.

The fourth category of radicals follows the rule that strokes of Kanji are generally written from top to bottom, meaning that they are written last. Let’s look at the radical 心 meaning “heart,” which is a variant of 忄from earlier. When you see it in the lower-half of a character, you know that the Kanji has something to do with emotions.

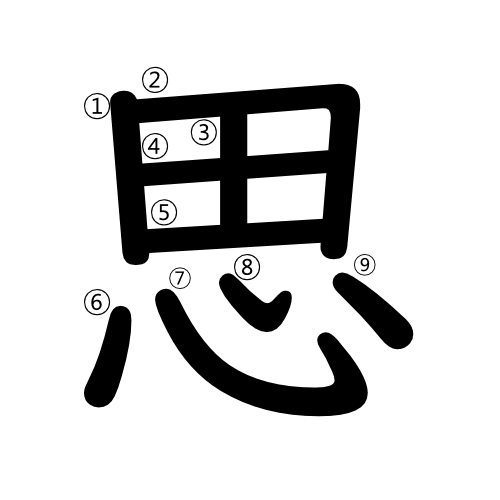

To demonstrate how these radicals are written, consider the character meaning 思 “think.”

To demonstrate how the radical 心 contributes meaning-wise to Kanji, consider the following characters.

忘 |

念 |

怒 |

想 |

恋 |

Forget |

Wish |

Anger |

Concept |

Romance |

Terminology Note: These radicals are known as あし in Japanese.

The fifth category of radicals follows the general guidelines of writing strokes from top-down and left-right. They appear hanging over the rest of the character in an r-shape. Let’s look at the radical 疒 meaning “sickness.” When you see it hanging over a character, you know that the Kanji has something to do with sickness.

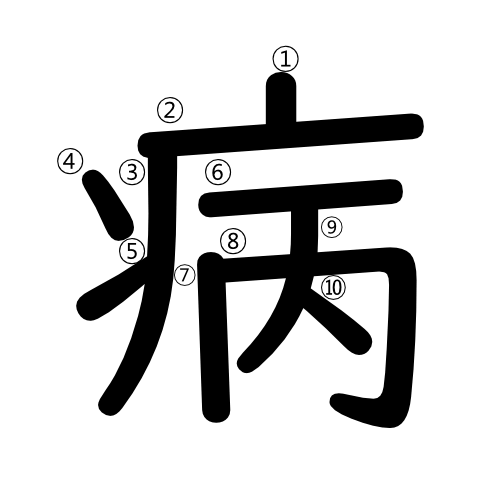

To demonstrate how these radicals are written, consider the character 病 meaning "disease".

To demonstrate how the radical 疒 contributes meaning-wise to Kanji, consider the following characters.

痛 |

疲 |

症 |

疫 |

癌 |

Pain |

Fatigue |

Symptom |

Epidemic |

Cancer |

Terminology Note: These radicals are known as たれ in Japanese.

The sixth category of radicals follows the general guidelines of writing stroke orders from top-down and left-right. Consequently, because they begin at the far-left side of a Kanji, they are written first. Let’s look at the radical 辶 meaning “movement.” When you see it wrapped to the left-side and bottom of a character in an l-shape, you know that the Kanji has something to do with movement/distance.

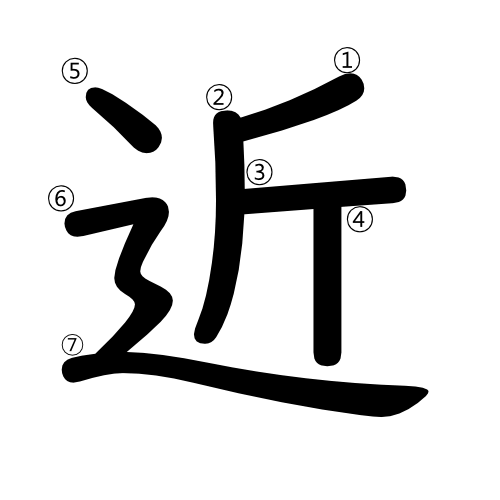

To demonstrate how these radicals are written, consider the character 近 meaning “close/nearby.”

To demonstrate how the radical 辶 contributes meaning-wise to Kanji, consider the following characters.

辺 |

迷 |

通 |

巡 |

這 |

Vicinity |

Lost |

Passing Through |

Patrol |

Crawl |

Variant Note: The radical 辶 can alternatively be seen as 辶 like in the Kanji above for “crawl.” The extra dot appears in not as common characters.

Terminology Note: These radicals are known as にょう in Japanese.

The seventh and final category of radicals all enclose the rest of the character they’re in. Technically, categories 5 and 6 can be seen as enclosure radicals, but they’re conventionally treated separately. Various kinds of enclosure radicals exist. They can either fully enclose the radical like the icon above or appear like the following icons:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Though stroke order depends on what sub-type the character is, they all follow the general principles discussed.

Let’s look at the radical 囗 meaning “enclosure.” When you see it to surrounding the entirety of a character, you know that the Kanji has something to do with some confined entity.

To demonstrate how these radicals are written, consider the character 回 meaning “revolve.”

To demonstrate how the radical 囗 contributes meaning-wise to Kanji, consider the following characters.

国 |

囲 |

固 |

図 |

囚 |

Country |

Surround |

Harden |

Map |

Prisoner |

Other example radicals of this category include 門 (gate), 凵 (open box), 匚 (on-side enclosure) 冂 (upside-down box), and 勹 (wrapping enclosure). Of these, all but the first are nearly purely elemental, providing the full shape to the character it is a part of. Below are some example characters utilizing these radicals.

聞 |

画 |

同 |

匂 |

区 |

Hear |

Picture |

Same |

Fragrant |

Ward |

問 |

缶 |

冊 |

色 |

医 |

Question |

Can |

Book |

Color |

Doctor |

Terminology Note: These radicals are known as かまえ in Japanese.

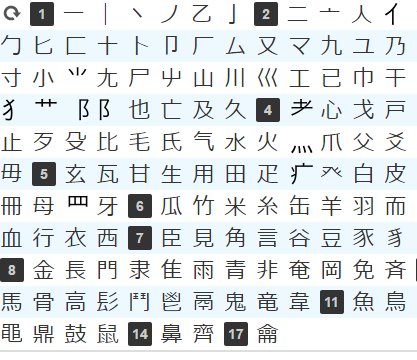

The chart below, extracted from www.jisho.org, displays all 214 radicals according to their stroke count. There is no need to look up each and every radical, nor is there any need to necessarily learn what their names are or all the Kanji made with them. There is far too much information for that to be possible or practical. Treat this as a mapping of the knowledge to be acquired on your journey.

In Lesson 6, we learned that Kanji are used to write units of meaning. Each character has one or more meanings, and their components (radicals) help the reader guess what those meanings are. Whereas the last lesson focused on learning about what Kanji are, this lesson will be about how to read them. Before we learn about how pronouncing Kanji works, we’ll need to first learn about the different kinds of Kanji that exist. This will help you figure out how to read Kanji more than you may think!

Kanji come in four main kinds based on what they represent and how. Originally, Kanji all began as pictographic representations of what they meant. The ancient Chinese took it upon themselves to turn pictures into meaningful symbols, and over many centuries, those symbols evolved into the Kanji we know today.

Pictograms

Pictograms are the direct descendants of these ancient depictions. Although highly stylized, many pictographic Kanji still greatly resemble what they represent. Below are some examples.

日 |

月 |

山 |

鳥 |

木 |

Sun |

Moon |

Mountain |

Bird |

Tree |

魚 |

川 |

貝 |

口 |

龍 |

Fish |

River |

Shellfish |

Mouth |

Dragon |

Ideograms

Whereas pictograms are depictions of concrete entities, ideograms are depictions of abstract entities. This is the only difference between the two. Below are some examples.

一 |

二 |

三 |

上 |

下 |

One |

Two |

Three |

Up |

Down |

天 |

今 |

母 |

音 |

立 |

Heaven |

Now |

Mother |

Sound |

Standing |

Compound Ideograms

Compound ideograms are the logical next step after simple ideograms. As implied by the name, they are created by combining radicals together to express a more complex meaning. The meaning is always abstract to some degree. Below are some examples.

林 |

森 |

炎 |

明 |

信 |

Woods |

Forest |

Flame |

Bright |

Believe |

Tree + Tree |

Tree + Tree + Tree |

Fire + Fire |

Sun + Moon |

Person + Word |

死 |

比 |

光 |

男 |

休 |

Death |

Compare |

Light |

Man |

Rest |

Bones + Person |

Person + Person |

Fire + Person |

Rice Field + Strength |

Person + Tree |

Semasio-Phonetic Characters