ホーム → 文法 → imabi → imabi veteran 2

第366課: Phonology I: Basic Information

第367課: Phonology 1.5: Consonants

第368課: Phonology II: Pitch (高低アクセント)

第370課: Phonology IV: 露出形 VS 被覆形

第371課: Phonology V: 撥音添加 & 撥音化

四字熟語 literally means "four character compound word". Technically, the term refers to all words made up of four characters. In a narrow-sense, the word refers to four character set expressions. That is what we will be discussing. For academic punctuality, the term "四字成語" is preferred because it means "four character set phrase". However, most people refer to them as "四字熟語". Due to their origin, most can also be called "四字漢語".

Japanese people will easily tell you that the following is a set phrase.

弁慶の泣き所

弁慶 means "strong man" and 泣き所 means "place where one cries". Together, the phrase refers to the shin. If you are kicked in the shin, even if you are a strong man, you are going to cry.

Idioms are rated by "idiomaticity"--how idiomatic something is. Every Japanese person knows 四面楚歌 (to be surrounded by enemies on all four sides) and 波瀾万丈 (stormy and full of drama). Phrases like 大学教育 (college education) are non-idiomatic. The idiomatic ones, though, are important to entrance exams in Japan, and they're often used in showing off to other people.

Again, the term normally refers to such words that deviate from a literal direct translation. Some compounds create a problem. For example, many idioms in Japanese have been introduced through direct translation.

| A 四字熟語 |

教室崩壊 | きょうしつほうかい | Destruction of the classroom |

| A Generic Idiom |

氷山の一角 | ひょうざんのいっかく | Tip of the iceberg |

| Idiom of the Body | 鼻の差で | はなのさで | By a nose |

To the English speaker, these expressions are no doubt idiomatic. As for the typical 四字熟語, they are not 'deviant' from the original definition. Most 四字熟語 come from Buddhist texts/Chinese literature.

It is to note that non-idiomatic (four character) expressions can over time obtain an idiomatic usage. 一時停止, which means "suspension", can now describe a guy stopping traffic because he won't go.

The 6 Sources

At times, 四字熟語 originating from Chinese have deviated in meaning. 七転八倒(しちてんばっとう) means "writhing in agony" in Japanese and "very confused" in Chinese. There is also obvious significant phonetic deviation.

You aren't required to memorize them all, but they are great practice. There isn't a particular ordering of the idioms. 一刀両断(いっとうりょうだん) 色即是空(しきそくぜくう) 手前味噌(てまえみそ) 付和雷同 暖衣飽食(だんいほうしょく) 一期一会(いちごいちえ) 美人薄命(びじんはくめい) 月下氷人(げっかひょうじん) 唯我独尊(ゆいがどくそん) 二股膏薬(ふたまたごうやく) 一石二鳥(いっせきにちょう) 呉越同舟(ごえつどうしゅう) 順風満帆(じゅんぷうまんぱん) 悪因悪果(あくいんあっか) 弱肉強食(じゃくにくきょうしょく) 寂滅為楽(じゃくめついらく) 色恋沙汰(いろこいざた) 酔生夢死(すいせいむし) 十人十色(じゅうにんといろ) 朝三暮四(ちょうさんぼし) 異体同心 会者定離 生者必滅 我田引水 五里夢中 古色蒼然 羊頭狗肉

|

黒風白雨(こくふうはくう) Black-wind-white-rain 1. Sudden rain shower in a dust storm 高山流水(こうざんりゅうすい) 花鳥風月 三々五々(さんさんごご) 一望千里(いちぼうせんり) 五風十雨(ごふうじゅうう) 九死一生(きゅうしいっしょう) 五十知命(ごじゅうちめい) 朝雲暮雨(ちょううんぼう) 三千世界(さんぜんせかい) 一文半銭(いちもんはんせん) 一文不通(いちもんふつう) 一陽来復(いちようらいふく) 一利一害(いちりいちがい) 一挙一動(いっきょいちどう) 一死報国(いっしほうこく) 浅学非才(せんがくひさい) 円満具足(えんまんぐそく) 再三再四(さいさんさいし) 人心一新(じんしんいっしん) 一心同体(いっしんどうたい) 一路平安(いちろへいあん) 一路順風(いちろじゅんぷう) 心機一転(しんきいってん) 意気投合(いきとうごう) 才子多病(さいしたびょう) 九牛一毛(きゅうぎゅういちもう) 一衣帯水(いちいたいすい) 清風明月(せいふうめいげつ) 純一無雑(じゅんいちむざつ) 下意上達(かいじょうたつ) 急転直下(きゅうてんちょっか) 悠々自適(ゆうゆうじてき) 海千山千(うみせんやません) 乾坤一擲(けんこんいってき) 厚顔無恥(こうがんむち) 傍目八目 |

| 一分一厘 | いちぶいちりん | Not even a bit |

| 一網打尽 | いちもうだじん | Wholesale arrest |

| 暗雲低迷 | あんうんていめい | Dark clouds hanging low |

| 曖昧模糊 | あいまいもこ | Ambiguous |

| 悪戦苦闘 | あくせんくとう | Hard struggle |

| 一瞬絶句 | いっしゅんぜっく | Rendered speechless for a moment |

| 一生懸命 | いっしょうけんめい | With all one's might |

| 一心不乱 | いっしんふらん | With heart and soul |

| 一体全体 | いったいぜんたい | What on earth? |

| 迂闊千万 | うかつせんばん | Very careless |

| 宇宙開闢 | うちゅうかいびゃく | Since the dawn of time |

| 容貌端正 | ようぼうたんせい | To have handsome and clean-cut features |

| 有史以来 | ゆうしいらい | Since the dawn of history |

| 和洋折衷 | わようせっちゅう | A blending of Japanese and Western styles |

| 和光同塵 | わこうどうじん | Wise men softening their light while with the mundane world |

| 老少不定 | ろうしょうふじょう | Death comes to old and young alike |

| 劣弱意識 | れつじゃくいしき | Inferior complex |

| 縷々綿々 | るるめんめん | To go on and on in tedious detail |

| 流転生死 | るてんしょうじ | The cycle of transmigration |

| 風声鶴唳 | ふうせいかくれい | To be frightened by the slightest noise |

| 風林火山 | ふうりんかざん | Swift as wind, quiet as forest, fierce as fire, and immovable as mountains |

| 武運長久 | ぶうんちょうきゅう | Continued luck in the fortunes of war |

| 複雑多岐 | ふくざつたき | Labyrinthine |

| 表裏一体 | ひょうりいったい | The two sides of the same coin |

| 比翼連理 | ひよくれんり | Perfect conjugal harmony between husband and wife |

| 百人百様 | ひゃくにんひゃくよう | So many men, so many ways |

| 眉目秀麗 | びもくしゅうれい | Having a handsome face |

| 飛耳長目 | ひじちょうもく | Being well-versed on something |

| 煩悶懊悩 | はんもんおうのう | Anguish |

| 万緑一紅 | ばんりょくいっこう | One red flower standing out in a see of green vegetation |

| 万事承知 | ばんじしょうち | Being well aware of |

| 八方美人 | はっぽうびじん | A woman who looks beautiful from all angles |

| 拈華微笑 | ねんげみしょう | Heart-to-heart communication |

| 如是我聞 | にょぜがもん | Thus I hear |

| 如露如電 | にょろにょでん | Existence is as incorporeal as the morning dew or flash of lightning |

| 南無八幡 | なむはちまん | I beseech your aid against my enemy! |

| 内剛外柔 | ないごうがいじゅう | Being gentle on the outside but tough on the inside |

| 土崩瓦解 | どほうがかい | Complete collapse |

| 道聴塗説 | どうちょうとせつ | Shallow-minded mouthing of secondhand information |

| 闘志満々 | とうしまんまん | Brimming with fighting spirit |

| 東西古今 | とうざいここん | All times and places |

| 桃紅柳緑 | とうこうりゅうりょく | The beautiful scenery of spring |

| 同工異曲 |

どうこういきょく | Different in appearance but the same in content |

| 天網恢恢 | てんもうかいかい | Heaven's vengeance is slow but sure |

| 恬淡虚無 | てんたんきょむ | Rising above the trivia of life and remaining calm and selfless |

| 天真流露 | てんしんりゅうろ | Manifestation of one's natural sincerity |

| 天地晦冥 | てんちかいめい | The world is covered in darkness |

| 天空海闊 | てんくうかいかつ | The open sky and serene sea |

| 天下泰平 | てんかたいへい | Peaceful and tranquil |

| 痛快淋漓 | つうかいりんり | To be extremely delightful |

| 痴話喧嘩 | ちわげんか | Lover's quarrel |

| 跳梁跋扈 | ちょうりょうばっこ | Evildoers being rampant and roaming at will |

| 寵愛一身 | ちょうあいっしん | To stand highest in one's master's favor |

| 忠言逆耳 | ちゅうげんぎゃくじ | Good advice is harsh to the ear |

| 躊躇逡巡 | ちゅうちょしゅんじゅん | Hesitation and vacillation |

| 魑魅魍魎 | ちみもうりょう | All sorts of weird creatures |

| 着眼大局 | ちゃくがんたいきょく | To take a broad view of things |

| 智慧不惑 | ちえふわく | A wise man never wavers |

| 知行合一 | ちこうごういつ | The doctrine of the unity of knowledge and action |

| 単刀直入 | たんとうちょくにゅう | Going right to the point |

| 男尊女卑 | だんそんじょひ | Male domination of women |

| 多岐亡羊 | たきぼうよう |

Truth is as hard to find as a sheep lost in a vast plain |

| 大漁貧乏 | たいりょうびんぼう | Impoverishment of fisherman due to a bumper catch |

| 大胆巧妙 | だいたんこうみょう | Bold and clever |

| 大山鳴動 | たいざんめいどう | A big fuss over nothing |

| 大器晩成 | たいきばんせい | Great talents mature late |

| 則天去私 | そくてんきょし | Following heaven and abandoning self |

| 造反有理 | ぞうはんゆうり | To rebel is justified |

| 先憂後楽 | せんゆうこうらく | Hardship now, pleasure later |

| 戦々恐々 | せんせんきょうきょう | To be filled with trepidation |

| 絶体絶命 | ぜったいぜつめい | Desperate situation |

| 切磋琢磨 | せっさたくま | Cultivating one's mind by studying hard |

| 世上万般 | せじょうばんぱん | Everything in this world |

| 青天白日 | せいてんはくじつ | To be cleared of all charges |

| 正邪善悪 | せいじゃぜんあく | Right and wrong |

| 政権亡者 | せいけんもうじゃ | One who is obsessed with political power |

| 酔眼朦朧 | すいがんもうろう | With drunken eyes |

| 垂涎三尺 | すいぜんさんじゃく | Avid desire |

| 衰退一途 | すいたいいっと | Being on the wane |

| 頭寒足熱 | ずかんそくねつ | Keeping the head cool and the feet warm |

| 人馬一体 | じんばいったい | Unity of rider and horse |

| 心頭滅却 | しんとうめっきゃく | Clearing one's mind of all mundane thoughts |

| 神色自若 | しんしょくじじゃく | Perfect composure |

| 心身一如 | しんしんいちにょ | Body and mind as one |

| 辛酸甘苦 | しんさんかんく | Hardships and joy |

| 支離滅裂 | しりめつれつ | Incoherent |

| 諸行無常 | しょぎょうむじょう | All worldly things are transitory |

| 四面楚歌 | しめんそか | To be surrounded by enemies on all sides |

| 生者必滅 | しょうじゃひつめつ | All living things must die |

| 純真無垢 | じゅんしんむく | Pure and innocent |

| 秋風落莫 | しゅうふうらくばく | Forlorn and helpless |

| 遮二無二 | しゃにむに | Recklessly |

| 詩人墨客 | しじんぼっかく | Poets and artists |

| 残念無念 | ざんねんむねん | What a pity! |

| 昨非今是 |

さくひこんぜ |

Complete reversal of values |

諺(ことわざ), proverbs, are often short sayings, 言い習わし. A proverb shows some sort of virtue, a common truth that anyone can relate to. A proverb may also show moral, satire, truth, and a whole array of important cultural items in a short and concise way. Free translation is often needed to make them sensible to English speakers. You don't have to be Japanese to learn Japanese proverbs. This is a bigoted argument that you should never listen to. If you're human and are capable of acquiring new information, you can learn Japanese proverbs.

The first sentence of each example will be in Japanese script. The second will be the same sentence in かな. The third sentence shows the literal translation and the fourth sentence shows the idiomatic or general translation. If anymore information needs to be made about a given expression, a fifth line will be used.

漢字 to learn this week: 鳶、鰹、鷲、鷗、鱒、髭、麹、宏、蜃、禽、麿、蟻、雹、豹、賑、藁、虻、蝦、蕊、葱

案ずるより生(う)むが易し。 天は自ら助くるものを助く。 鰻(うなぎ)の寝床。 全ての道はローマに通ず。 見ぬが花。 寝耳に水 一年の計は元旦にあり。 魚心あれば水心 一を聞いて十を知る。 猫に小判。 Cultural Note: A koban is an oval coin used in currency in Japan made either of gold or silver. 漁夫の利 毒をもって毒を制す。 宝の持ち腐れ 尻切れトンボ 七転び八起き。 ペンは剣よりも強し。 どんぐりの背比べ。 言わぬが花。 諸刃の剣 火のないところには煙は立たぬ。 藪を突付いて蛇を出す。 豚に真珠。 鶴の声 月夜に提灯(ちょうちん)。 井の中の蛙大海を知らず。 馬の耳に念仏。 縁側の下の力持ち。 ローマは一日にして成らず。 口は禍の元。 良薬口に苦し。 借りてきた猫。 住めば都。 多々益々弁ず。 河童も川流れ。 蚤(のみ)の夫婦 上には上がある。 石の上にも三年。 落花(らっか)枝に帰らず。 沈む瀬あれば浮かぶ瀬あり。 為せば成る。 乞食を三日すればやめられぬ。 急がば回れ。 噂をすれば影(がさす) 前門の虎、後門の狼 弘法筆を択ばず。 早起きは三文の得。 年寄りの冷や水。 来年のことを言えば鬼が笑う。 光陰(こういん)矢の如し。 一寸先は闇。 身から出た錆 捕らぬ狸の皮算用をするな。 過ぎたるはなお及ばざるが如し。 転石苔(てんせきこけ)を生せず。 塵(ちり)も積もれば山となる。 損して得取る。 三度目の正直 釈迦に説法 脳ある鷹(たか)は爪(つめ)を隠す。 頭を隠して尻(しり)を隠さず。 三人寄れば文殊の智慧(ちえ)。 溺れる者は藁(わら)をも掴む。 仏の顔も三度。 悪妻は六十年の不作。 触らぬ神に祟りなし。 悪事千里を走る。 枯れ木も山の賑わい 猫も杓子(しゃくし)も 旅の恥は掻き捨てて。 青雲の志。 雲泥の差。 初心忘るべからず。 小人閑居して不善を為す。 二兎を追う者は一兎をも得ず。 |

門前市(もんぜんいち)をなす。 他人の飯を食う。 情けは人の為ならず。 餅は餅屋 宵越しの金を持たぬ。 青年重ねて来たらず。 腐っても鯛(たい) 石の上にも三年 李下瓜田( りかかでん) 三つ子の魂百まで かわいい子には旅をさせよ。 すずめの涙 焼餅焼くとて手を焼くな。 李下の冠を正さず。 腹八分目に医者いらず 出る杭は打たれる。 知らぬが仏。 Good fortune comes in the laughing gate. Good fortune and happiness will come to the home of those who smile. 猿も木から落ちる。 泥棒を捕らえて縄を綯(な)う。 人は見かけによらぬもの 花より団子。 井の中の蛙(かわず)大海を知らず。 鳴く猫はねずみを捕らぬ。 濡れぬ先の傘。 弘法(こうぼう)にも筆の誤り。 寄らば大樹の陰 目には目を、歯には歯を。 河童の川流れ。 石橋を叩いて渡る。 立つ鳥跡を濁さず。 蓼(たで)食う虫も好き好き。 喉元(のどもと)過ぎれば熱さを忘れる。 時は金なり。 人のふり見て我がふり直せ。 生兵法(なまびょうほう)は大怪我の基(もと)。 隣の芝生は青い。 隣の花は赤い。 郷(ごう)に入っては郷に従え。 焼け石に水。 男心と秋の空。 玉に瑕(きず) 二階から目薬 駄目で元々 仏の顔も三度 痘痕(あばた)も笑窪 匙(さじ)を投げる。 鴨が葱(ねぎ)をしょってくる。 無い袖(そで)は振れぬ。 濡れ衣を着せる。 覆水盆に返らず。 終わりよければ全てよし。 泣き面に蜂(はち)。 叩けば埃が出る。 頭隠して尻隠さず。 虻蜂(あぶはち)取らず 犬猿の仲。 挨拶(あいさつ)は時の氏神(うじがみ) 千里の道も一歩から 惚れてしまえば痘痕(あばた)も笑窪。 堪忍袋の緒が切れる。 麻の中の蓬(よもぎ)。 朱に交われば赤くなる。 絵に描いた餅(もち)。 門前の小僧習わぬ経を読む。 前事を忘れざるは後事の師なり。 秋茄子(あきなす)は嫁に食わすな。 備えあれば憂いなし。 袖振り合うも他生(たしょう)の縁。 猫の首に鈴をつける。 糠(ぬか)に釘(くぎ)。 餅は餅屋。 二足の草鞋(わらじ)。 猫を追うより皿を引け。 |

There are several intransitive verb forms unique to specific areas of Japan. There are many verbs with several transitive forms. However, as we have seen in previous lessons, they're all used extensively. They may just not mean the same things. The intransitive verb forms we'll see in this lesson are almost exclusively dialectal. The interesting thing about these words is that they fill in lexical gaps hard to explain away through 標準語. Some of them have weird origins, which makes things even more interesting. We'll even learn about a conjugation unique to only one dialect! Let's begin.

Because the process of deriving intransitive and transitive verbs is not completely straightforward, there is variation in how you should express transitivity on a case by case basis. Below are some common regional variation that you may encounter. The arrow indicates correct, Standard Japanese.

1. ガムが

靴

にくっつかっている。 (東北弁) → ガムが靴にくっついている。

Gum is stuck to my shoes.

Form Note: Speakers who use くっつかる use it as a more emphatic version of くっつく. This is one of those words which if you use it, you may not even notice it's dialectical until you realize no one else in the country uses it.

2.

解

が

求

まる。 → 解が求められる・解が

整

う・解にたどり着く。

For a solution to be solved.

Form Note: 求まる has existed but has fallen out of use except by some people in math. When people hear it for the first time, they are often taken back and think it is grammatically incorrect.

3. 単語が覚わった。 (

名古屋

~

岐阜

) → 覚えきった。

I got the words down. (memory)

Form Note: This form should be impossible as this would mean that it ultimately derived from 覚える + ある. 覚える shares 思える, and both can be classified as verbs of spontaneity. Other verbs like this include 見える and 聞こえる. They describe things that happen naturally on their own. But, 覚わる, a form which is supposed to be impossible accidentally came about and is used a lot in some areas of Japan. Another word that came about from a similar mistake is 報われる. The verb for "to reward" was 報ゆ. Rather than using the passive ending normally, which results in the modern 報いられる, the verb was analyzed as being 報う instead. Today, 報う, 報いる, 報われる, and 報いられる exist. The spontaneity verbs ended in ゆ in the past as well, so this may have something to deal with 覚わる coming about.

4.

筋肉

が

鍛

わる。 (名古屋 Area?) → 筋肉が鍛えられる。

For one's muscles to be built.

5. あごが鍛わった気がする。

I feel like my jaw is hardened up.

6. ロープが

凍

って

結

ばらない。

→

(

飛騨弁

) ロープが凍って結ぶことができない。

The rope froze and I can't get a knot in it.

The Auxiliary Verb ~さる: Anti-Causative/Spontaneous Occurrence

In 北海道弁 and other northern dialects, you may see さる attached to the 未然形 of verbs to create intransitive verb pairs. Examples of this include くっつかさる, 溶かさる = 溶ける, and 終わらさる = 終わる. However, it is not the case that speakers here don't use the regular intransitive forms. So, what exactly is さる used for? First, let's go over its conjugation.

| 一段 Verbs | 未然形 + らさる | 食べらさる |

| 五段 Verbs | 未然形+ さる | 読まさる |

This is actual used to create spontaneity phrases just like 見える. Because these words are intransitive too, this is yet another means of 自動詞化. However, this is completely unique to 北海道弁. This conjugation doesn't exist in any other dialect area. The meaning is along the lines of not intending to do something, but conditions proceed in a way that you find yourself naturally in the situation.

7. この小説は面白くて、どんどん読まさります。

This book is so interesting that I just end up reading more and more of it.

This conjugation is perfect for not implying one's incapability or incompetence when used in the negative ~(ら)さんない. For instance, say your pen doesn't work. If you were to say in Standard Japanese このペンは書けない. It's unclear why you can't use the pen. Is it because the ink is out or because somehow you're too stupid to know how to use the pen? In 北海道弁, you can place all the blame on the natural order of things by saying the following.

8. このペン書かさんない。

This pen won't write.

Due to the unique fixation of 漢字 to Japanese, a complex set of readings with different origins has produced the hardest method of reading 漢字 of all languages that use 漢字. This lesson will delve deeper into the 音訓 puzzle. A firm understanding of how to read 漢字 affects how efficiently you can acquire new words and new characters.

漢字 are called ideograms, symbols that display meaning. However, their shapes alone don’t produce meaning itself. Words are produced by the human mind, and these words are attributed to these highly crafted arrangements of strokes we call 漢字. After all, only a human can understand 水 as water. This 漢字 to Mandarin Chinese speakers has the sound Shuǐ. This is what these people think when they see water and this symbol. However, in Japanese, there is more than one reading to this character. There is the native word for water mizu. There is also the 音読み from Chinese SUI. Both are attributed to 水.

Thus, in Modern Japanese, there are two language units distinguished in reading 漢字. 音, the sounds of characters as borrowed from various stages of Chinese languages, and 訓, native vocabulary attributed to these foreign characters.

Although the history of 音読み is really complicated and the Japanese sound system has also changed over time, 音読み were in large part assimilated to the existing sound constraints of Japanese. Over time, this system of two kinds of readings, with characters often having more than one of each, has solidified and become what it is today.

As you have encountered numerous times no doubt in your Japanese studies, many 漢字 have more than one 音読み. This is because, as mentioned earlier, they come from different stages of Chinese. All words with 音読み are Sino-Japanese unless simply used for phonetic purposes. For example, although the word 世話 is pronounced as SEWA with 音読み, it is actually a native word.

The Four Kinds of 音読み

There are four kinds of 音読み generally recognized. Unlike other languages utilizing Chinese characters, older readings did not get totally replaced with new ones in Japanese. Rather, they are used together in a complex amalgam. As far as 音読み are concerned, many readings can be guessed on because of phonetics in the characters. As you will see, though, many shifts have occurred in these readings. This has all lead to many characters having the same readings.

呉音: Sounds of Wu

The first wave of readings are called 呉音. These readings are the oldest and come from the Wu Dynasty. They entered Japanese during the 5th to 6th centuries. Many Buddhist and Ritsuryou System (律令) terms have these readings as well as many for basic vocabulary like SAN for 山.

Historical Note: The 律令 was the fundamental set of codes by which constituted in large part the early Japanese political system.

| 世間 | SEKEN | World; society | 末期 | MATSUGO | Hour of death |

| 男女 | NAN'NYO | Men and women | 正体 | SHOUTAI | True identity |

| 経文 | KYOUMON | Sutra | 下人 | GENIN | Menial |

| 極楽 | GOKURAKU | Paradise | 正直 | SHOUJIKI | Honest |

| 成就 | JOUJU | Success | 会釈 | ESHAKU | Nod; salutation |

| 工夫 | KUFUU | Scheme | 祇園 | GION | Gion |

| 白衣 | BYAKUE | White robe | 金色 | KONJIKI | Gold color |

| 荼毘 | DABI | Cremation | 供米 | KUMAI | Rice offering |

Word Notes:

1. NAN'NYO is an old-fashioned reading of 男女.

2. Gion is the entertainment district of 京都.

3. BYAKUE is an old-fashioned reading of 白衣.

There were many alterations to the actual pronunciations used at the time in Wu China. For instance, final –t became –chi such as NICHI for 日. –ng, which didn’t exist in Japanese, was dealt with randomly, sometimes being replaced with a back vowel like I or U. Other times, it was dropped altogether. However, in rare instances this final –ng became preserved as a medial g. Ex. SUGOROKU 双六.

Historical Notes:

1. These readings are also sometimes called 対馬音 つしまおん・つしまごえ and 百済音 くだらおん・くだらごえ because it is said that a Paekje monk by the name of Houmyou 法名 read the Vimalakirti Sutra (維摩経) with 呉音 at Tsushima.

2. Also, it is believed by some due to no actual written evidence that these readings may have actually been Korean alterations to some form of Chinese as they were introduced to the Japanese via the Korean peninsula.

3. Paekje, which is called Kudara by the Japanese, is one of the ancient Korean kingdoms.

漢音: The Sounds of Han China

漢音 are readings borrowed during the 7th to 8th centuries in the Sui and Tang Dynasties. They were sent to Japan via emissaries. They were heavily propagated as the correct pronunciation of characters. Despite efforts by elites to eradicate呉音, they could not be taken out of already commonly used daily words with them. Thus, we have many characters to this day with more than one 音読み.

Several systematic changes can be seen when comparing 呉音 and 漢音. The most important phenomenon is denasalization that occurred in Chinese. In this sound change, the latter half of a nasal sound would become an oral sound. This would be reflected over into Japanese in the following ways.

| 馬 | MA → BA | 日 | NICHI → JITSU | 美 | MI → BI |

There are exceptional cases where nasal endings were retained during the borrowing process such as NEN for 年.

Another important phenomenon is the devoicing of voiced initials.

| 定 | JOU → TEI | 従 | JUU → SHOU | 勤 | GON → KIN |

It is important to remember that sound changes have also occurred in Japanese. So, these are the modern renderings of the readings. For instance, JOU for 定 was actually traditional spelled in かな as ぢやう. This would have reflected the pronunciation at the time. Also, keep in mind that despite efforts to propagate 漢音, not all such readings were able to displace 呉音.

For instance, the 漢音 of 和 and 話 is KWA, but this reading never made it to the present. Other similar instances did in this k-insertion. For example, 会’s E → KAI.

It would take too long to go through every detail for every 漢字. So, we will now switch focus to how 漢音 have become used. The overwhelming majority of 漢字 have 漢音, and they were further propagated during the Meiji Restoration by being used to coin hundreds of words. Although 呉音 continued to have overwhelming influence in Buddhist texts, there are some instances were certain sects read particular sutras in 漢音. For instance, the 理趣経 of the 真言宗 is read with 漢音. So, the famous starting of sutras 如是我聞 (Thus, I hear) is pronounced as JOSHIGABUN rather than the typical NYOZEGAMON, which uses 呉音.

Example Words:

| 末期 | MAKKI | Closing years; terminal | 経世 | KEISEI | Conduct of state affairs |

| 文人 | BUNJIN | Literary person | 土地 | TOCHI | Land |

| 幕府 | BAKUFU | Shogunate/bakufu | 内裏 | DAIRI | Imperial palace |

| 女児 | JOJI | Female child | 男女 | DANJO | Men and women |

| 白衣 | HAKUI | White robe | 老若 | ROUJAKU | Young and old |

| 口頭 | KOUTOU | Oral | 左右 | SAYUU | Left and right |

| 遠近 | ENKIN | Far and near | 兵隊 | HEITAI | Soldier |

| 達成 | TASSEI | Achievement | 質量 | SHITSURYOU | Mass |

Word Notes:

1. DANJO is the normal reading of 男女.

2. Notice how the different readings of 末期, まつご and まっき, have different meanings.

3. HAKUI is the normal reading of 白衣.

4. 老若 may also be seldom read with the 呉音 ROUNYAKU.

唐音: T’ang Sounds

Although they weren’t actually borrowed during the T’ang Dynasty, 唐音 were borrowed later from the Kamakura to the Edo Periods. They are generally rare and seen mainly in Zen Buddhism, trade, food, and furnishing terminology.

Terminology Note: These sounds are also called 宋音・唐宋音.

| 布団 | FUTON | Futon | 納戸 | NANDO | Barn |

| 扇子 | SENSU | Folding fan | 北京 | PEKIN | Beijing |

| 南京 | NANKIN | Nanqing | 瓶 | BIN | Bottle |

| 行脚 | ANGYA | Pilgrimage | 普請 | FUSHIN | Construction; community activities |

| 箪笥 | TANSU | Dresser | 杜撰 | ZUSAN | Sloppy |

| 団栗 | DONGURI | Acorn | 炭団 | TADON | Charcoal briquette |

| 餡 | AN | Read bean paste | 湯麺 | TANMEN | Tang mian |

| 繻子 | SHUSU | Satin | 楪子 | CHATSU | Type of lacquerware |

| 杏子 | ANZU | Apricot | 椅子 | ISU | Chair |

| 石灰 | SHIKKUI | Plaster | 胡散 | USAN | Suspicious |

| 胡乱 | URON | Fishy | 橘飩 | KITTON | Mashed sweet potatoes |

| 暖簾 | NOREN | Shop entrance curtain | 饅頭 | MANJUU | Manjuu |

| 湯湯婆 | YUTANPO | Hot water bottle | 看経 | KANKIN | Silent reading of sutra |

| 明 | MIN | Ming Dynasty | 鈴 | RIN | Bell |

| 提灯 | CHOUCHIN | Paper lantern | 茴香 | UIKYOU | Fennel |

Word Note: SHIKKUI is now normally spelled as 漆喰. 石灰 is typically read with the 漢音 SEKKAI to mean "lime" as in limestone.

慣用音: Traditional Sounds

慣用音 are mishap readings that have somehow changed since being incorporated into Japanese. Important examples include the following.

| 立 | RYUU → RITSU | 輸 | SHU → YU |

| 攪拌 (Agitation) | KOUHAN → KAKUHAN | 執 | SHUU → SHITSU |

| 洗滌 (Washing) | SENDEKI → SENJOU | 涸渇 (Drying up) | KOKUKATSU → KOKATSU |

慣用音 Classification Controversy

Currently, any reading that deviates from 呉音, 漢音, and 唐音 are considered 慣用音. This means that several different situations are lumped together.

Change Influenced by 訓読み

At times, 音読み were manipulated due to 訓読み. For example, 早速 should be pronounced SOUSOKU but it is instead pronounced as SASSOKU, with the sa- coming from a native prefix seen in words like sanae 早苗 (rice seedlings) and saotome 早乙女 (young woman). There is also 奥意 OKUI (true intention) and 奥地 OKUCHI (hinterland) which should be OUI and OUCHI respectively, but the 音読み OU/IKU has changed to OKU for most speakers. Thus, these extraordinary readings have become labeled as 慣用音.

Changes to Final –フ

Many 音読み in traditional orthography ended in ふ. It is agreed by most scholars that f used to be p in Old Japanese, and eventually became ɸ by Middle Japanese. Due to this effect, readings such as てふ for 蝶 became ちょう.

Plosive and fricative sounds in the final position were preserved with 促音 in words like 合戦 KASSEN (match; engagement), 入声 NISSHOU (initial tone), and 法度 HATTO (ordinance). On the other hand, these finals were typically replaced with う. Thus, you get many common words like 合成 GOUSEI (synthesis), 甲子園 KOUSHIEN (Koshien), and 入賞 NYUUSHOU (winning a prize). There are also instances where ふ → つ. For instance, 立 RYUU → RITSU, 圧 OU → ATSU, 執SHUU → SHITSU. These changes from the original readings are still classified in many 漢和辞典 as 慣用音.

音読み Confusion

When a 漢字 has more than one 音読み and they have become specialized for particular meanings and the expected reading is not used, this accidental misuse of a reading is deemed to be a 慣用音. One of the best examples of this is 罷免 (discharge). 罷 is supposed to be read as HAI when the character is used to mean “to tire” and HI when used to mean “to stop”. Yet, instead of being read as HAIMEN, the word is read as HIMEN. Thus, this usage of HI is classified as a 慣用音.

Readings with Unknown Origins

There are also readings with unknown origins. These readings, despite obviously coming from Chinese variants, are lumped into the term 慣用音.

For example, 茶 is typically read as CHA, but this reading is not a 呉音, 漢音, or 唐音. In order, those readings are actually DA, TA, and SA. So, CHA is classified as a 慣用音. Another odd example is the reading PON for 椪. It is typically believed to be from Taiwanese, and all of its other readings are unknown. Thus, it is classified as a 慣用音.

Lots of Homophones

Due to the fact that so many waves of 音読み have been incorporated into Japanese with heavy simplification due to assimilation into the Japanese sound system, many words sound alike. Just typing こう results in dozens of options. There are a lot of homophones in Mandarin Chinese, but at least there is more variety in its phonology. Thankfully, the majority of homophones are avoided in the spoken language. Of course, there are exceptions. For example, the reading EKI for 駅, 益, 液, 易, and 役 are commonly used.

訓読み have not been immune to change. After all, if a language doesn't change, it’s dead. 訓読み are from native words, and the reason they exist is because the Japanese already had their own language when 漢字were introduced. Although there are plenty of 訓読み that have essentially not changed at all over the course of time such as yama 山 and kusa 草, others like 危 うい → 危

ない have.

Sino-Japanese 訓読み

There are actually some words of Chinese that were borrowed way before 漢字 were, and they are so integral in the language that they are viewed as native words. Important examples include the following.

| 馬 | うま | 銭 | ぜに | 梅 | うめ |

Number of 訓読み a Character

The number of 訓読み a character usually has also changed over time. As time progressed, most characters have come to have only one 訓読み. However, it still doesn't take much effort to find blatant anomalies like 生, which has lots of readings.

| 生きる | いきる | To live | 生- | なま- | Raw | 生む | うむ | To give birth |

| 生す | むす | To grow (moss) | 生す | なす | To give birth | 生う | おう | To spring up |

| 生{える・やす} | はえる・はやす | To cultivate | 生る | なる | To bear seed | 生 | き | Undilated |

| 生 | うぶ- | Innocent; birth- | 生 | -ふ | Thick growth |

Just to think, there are more irregularities and 音読み to keep in mind as well.

Kinds of Words with 訓読み

Typically, the majority of 訓読み are used to write independent words, with all of the examples such far being just that.

| 雨 | あめ | 雲 | くも | 日 | ひ | 火 | ひ | 喜び | よろこび |

| 歌う | うたう | 思い | おもい | 高い | たかい | 花 | はな | 鼻 | はな |

There are some that are etymologically compound words but have since been fixated to the point that they are treated as simple words.

| 湖 | みずうみ | 志 | こころざし | 快い | こころよい | 瞼 | まぶた |

| 炎 | ほのお | 橘 | たちばな | 睫 | まつげ | 雷 | かみなり |

There are also instances where several characters have received the same 訓読み. This shouldn't be surprising given how many 漢字 exist. The hardest part about this is that options typically have specific nuances, which causes correct spelling to be more difficult.

| はかる | 計る・測る・量る・諮る・図る・謀る |

| とる | 取る・捕る・執る・採る・撮る・獲る・摂る・盗る・録る |

Today, 訓読み are generally not used to write ancillary words such as particles and other function words. However, there are exceptions and many such words still do have 漢字 spellings.

| 迄 = まで | 也 = なり | 御 = おん・お・み- | 程 = ほど | 秤 = ばかり | 位 = くらい |

| 哉 = かな | 幾 = いく- | に就いて = について | 様に = ように | 事 = こと | 物 = もの |

Word Notes:

1. なり is the Classical copula.

2. ほど, ばかり, and くらい as particles are usually not written in 漢字.

3. 事 and 物 when used for more grammatical purposes are typically not written in 漢字.

4. Other speech modals like について and ように are usually only written in 漢字 in formal writing.

Loanwords with 訓読み

訓読 みmay also be loanwords and can be as 5 morae long, often caused by compound words as mentioned before. The reason why loanwords may sometimes be classified as 訓読み is because a lot of characters for things like measurements and stuff were coined during the Meiji Restoration. These, thus, would be 国字 (Japanese-made characters) and would otherwise be expected to not have 音読み.

Meters:「粉(デシメートル)」、「糎(センチメートル)」、「粍(ミリメートル)」 ― 「籵(デカメートル)」、「粨(ヘクトメートル)」、「粁(キロメートル)」

Liters:「竕(デシリットル)」、「竰(センチリットル)」、「竓(ミリリットル)」 ― 「竍(デカリットル)」、「竡(ヘクトリットル)」、「竏(キロリットル)」

Grams: 「瓰(デシグラム)」、「甅(センチグラム)」、「瓱(ミリグラム)」 ― 「瓧(デカグラム)」、「瓸(ヘクトグラム)」、「瓩(キログラム)」。「瓲(トン)」はおまけ。

送り仮名

Many 訓読み have 送りがな requirements. Despite government efforts, though, 送りがな is still rather random for lots of words. For instance, wakaru is typically spelled as 分かる. However, it can also be spelled as 分る, 判る, 解る, and 解かる.

Sound Changes

There also readings morphologically limited to certain situations. For instance, vowel shifts when creating compound words often cause many students to mispronounce words because they don’t understand them.

For instance, E → A and I → O are extremely common. They are also important to researchers that suggest Old Japanese had an 8 vowel system.

| 雨 + 雲 → あまぐも | 手 + 綱 → たづな | 手 + 紙 → てがみ | 木 + 霊 → こだま | 目+ ゆ+ 毛 → まゆげ |

As you can see, there is also voicing (連濁) to keep in mind, and these sound changes may not happen in all compounds as 手紙 suggests.

名乗り

There are also 訓読み called 名乗り that are used in names. A given name could be read in many ways. There are usually readings that are more prominent. The sheer number of 名乗り has actually gone down over time, but it still causes headaches for natives and learners on how to properly read a person’s name.

秀吉・秀義・英義・英吉・英喜・秀芳・英良・秀好・秀良・秀泰・栄良・英美・秀房・秀由・秀剛・秀嘉・秀衛・秀佳, etc. = ひでよし

The large majority of words, 音読み and訓読み are combined and used together. Furthermore, the majority of words with 音読み are used in compounds (熟語), and the majority of 訓読み are used in isolation or with 送りがな. However, there are instances of 音読み used in isolation, and there are also instances of 訓読み used in compounds.

Aside from this, the main issue is that there are times when they are combined and used together! There are two such instances. The first is when a compound is 音 and 訓 are compounded (重箱読み), and the second is when a compound is 訓 and 音 are compounded (湯桶読み).

重箱読み

重箱 is a multi-tiered box, and it has been used in the word 重箱読み because it is a perfect example of an 音 and 訓 combination. Other examples include the following.

| 路肩 | ROkata | Road shoulder | 番組 | BANgumi | TV program |

| 木目 | MOKUme | Grain of wood | 客間 | KYAKUma | Parlor |

| 台所 | DAIdokoro | Kitchen | 茶筒 | CHAzutsu | Tea caddy |

| 団子 | DANgo | Dumplings | 反物 | TANmono | Fabric |

| 額縁 | GAKUbuchi | Frame | 本屋 | HON'ya | Book store |

| 残高 | ZANdaka | Balance (bank) | 新顔 | SHINgao | New face |

| 職場 | SHOKUba | Work place | 役場 | YAKUba | Town hall |

湯桶読み

A 湯桶 is a pail-like wooden container used to carry and serve hot liquids, and it is used in the word 湯桶読み because it is a perfect example of a 訓 and 音 combination. Other examples include the following.

| 場所 | baSHO | Place | 身分 | miBUN | Social position |

| 消印 | keshi'IN | Postmark | 古本 | furuHON | Old book |

| 見本 | miHON | Sample | 夕刊 | yuuKAN | Evening edition |

| 荷物 | niMOTSU | Luggage | 踏台 | fumiDAI | Stool; stepping stone |

| 雨具 | amaGU | Rain gear | 薄化粧 | usuGESHOU | Light makeup |

| 高台 | takaDAI | High ground | 手帳 | teCHOU | Notebook |

| 手数 | teSUU | Bother | 鶏肉 | toriNIKU | Chicken (meat) |

| 闇市場 | yamiSHIJOU | Black market | 湯茶 | yuCHA | Hot water and tea |

| 野宿 | noJUKU | Sleeping outdoors | 大損 | ooZON | Major loss |

| 太字 | futoJI | Boldface | 細字 | hosoJI | Small type |

| 冬景色 | yukiGESHIKI | Snowy landscape | 雪化粧 | yukiGESHOU | Covered in snow |

送り仮名 in its simplest understanding is かな used for conjugation purposes. However, the rules for 送り仮名are not quite set in stone. Though variant spellings in this regard are disappearing in replace of one spelling, literature is still pervaded with variant spellings.

Natives still show relative inconsistency in the matter. This is because guidelines by the government have not been crafted to the point that they should touch on individual spelling practices.

Resource Note: Much of this information is adopted from the Ministry of Education guidelines for 送り仮名 usage, which can be found at http://www.bunka.go.jp/kokugo_nihongo/joho/kijun/naikaku/okurikana/index.html.

In writing words in 漢字 and making clear what reading should be used, it has become orthodox to affixかな. For instance, in order to read 送 as おくる rather than ソウ or even some conjugation likeおくらない, る is affixed to it. However, things that do have 漢字spellings but are replaced with かな, 交ぜ書き, is not called 送り仮名.

Rules for properly using 送り仮名 have been passed by the government, and it wouldn’t be surprising if these guidelines were modified again. However, even the preface of the guidelines published in 1973 admits that these rules do not pervasively apply to every aspect of Japanese. For instance, standards in science, the arts, and special fields are immune to having to follow these rules, which is why there have been plenty of mentions of how to address these situations thus far.

However, it is without a doubt that these guidelines do play a substantial role in orthography used in broadcast, official documents, newspapers, etc.

In studying the use of 送り仮名, you must first distinguish words in two groups: those that conjugate and those that don’t. Compound words are also important to consider. Though these different faces of 送り仮名 are rather complex, there are basic principles to keep in mind that work for the majority of cases.

If a word conjugates, it will have 送り仮名 affixed.

| 憤る | いきどおる | To resent | 承る | うけたまわる | To undertake; to hear/know (humble) |

| 書く | かく | To write | 生きる | いきる | To live |

| 考える | かんがえる | To think | 陥れる | おちいれる | To trick into; assault (castle); drop into |

| 助ける | たすける | To help | 催す | もよおす | To hold (event); feel (sensation) |

| 荒い | あらい | Rough; wild | 潔い | いさぎよい | Gallant; unsullied |

| 賢い | かしこい | Wise | 濃い | こい | Thick |

| 薄い | うすい | Thin | 主な | おもな | Main |

Irregularities

1. Adjectives that end in しい・じい such as 美しい and 凄まじい(terrible) were historically 美し and 凄まじ. So, this is why し・じ haven’t been dropped in the spellings.

2: Native suffixes that create adjectives such as か, らか, andやか are also left as 送り仮名.

| 細かな | こまかな | Fine; detailed | 静かな | しずかな | Quiet | 暖かな | あたたかな | Warm |

| 平らかな | たいらかな | Level; peaceful | 柔らかな | やわらかな | Tender; meek | 和やかな | なごやかな | Harmonious |

| 健やかな | すこやか | Vigorous | 鮮やかな | あざやかな | Vivid; adroit | 穏やかな | おだやかな | Calm; gentle |

3: The following words are irregular.

| 明らむ | あからむ | To break dawn | 味わう | あじわう | To taste; savor |

| 哀れむ | あわれむ | To pity | 慈しむ | いつくしむ | To be affectionate to |

| 教わる | おそわる | To be taught | 脅かす | おどかす・おびやかす | To menace |

| 関わる | かかわる | To be concerned with | 食らう | くらう | To eat/drink (Vulgar) |

| 異なる | ことなる | To differ | 逆らう | さからう | To defy |

| 捕まる | つかまる | To be caught | 群がる | むらがる | To swarm; gather |

| 和らぐ | やわらぐ | To be mitigated | 揺する | ゆする | To shake; jolt |

| 明るい | あかるい | Bright | 危ない | あぶない | Dangerous |

| 危うい | あやうい | Dangerous | 大きい | おおきい | Big |

| 少ない | すくない | Few | 小さい | ちいさい | Small |

| 冷たい | つめたい | Cold | 平たい | ひらたい | Flat |

| 新たな | あらたな | New | 同じ | おなじ | Same |

| 盛んな | さかんな | Popular; enthusiastic | 平らな | たいらな | Flat; smooth |

Derivations are included in 送り仮名.

1. Conjugations/derivations of verbs.

| Derivation | Base Word | Derivation | Base Word | Derivation | Base Word |

| 動かす | 動く | 照らす | 照る | 語らう | 語る |

| 浮かぶ | 浮く | 生れる | 生む | 押える | 押す |

| 捕える | 捕る | 勇ましい | 勇む | 輝かしい | 輝く |

| 喜ばしい | 喜ぶ | 晴れやかだ | 晴れる | 及ぼす | 及ぶ |

| 積もる | 積む | 聞こえる | 聞く | 頼もしい | 頼む |

| 起こる | 起きる | 落とす | 落ちる | 暮らす | 暮れる |

| 冷やす | 冷える | 当たる | 当てる | 終わる | 終える |

| 変わる | 変える | 集まる | 集める | 定まる | 定める |

| 連なる | 連ねる | 交わる | 交える | 混ざる・混じる | 混ぜる |

| 恐ろしい | 恐れる | 恨めしい | 恨む | 痛ましい | 痛む |

2. Words including an adjectival root.

| Derivative | Base Word | Derivative | Base Word | Derivative | Base Word |

| 重んずる | 重い | 若やぐ | 若い | 怪しむ | 怪しい |

| 悲しむ | 悲しい | 苦しがる | 苦しい | 確かめる | 確かだ |

| 重たい | 重い | 憎らしい | 憎い | 古めかしい | 古い |

| 細かい | 細かだ | 柔らかい | 柔らかだ | 清らかだ | 清い |

| 高らかだ | 高い | 寂しげだ | 寂しい | 可愛げ | 可愛い |

3. Things with nouns in them.

| Verb | Base Noun | Verb | Base Noun | Verb | Base Noun | Verb | Base Noun |

| 汗ばむ | 汗 | 先んずる | 先 | 春めく | 春 | 後ろめたい | 後ろ |

許容: When there is no worry of being misread, 送り仮名 may be abbreviated as in the following words.

| 浮かぶ → 浮ぶ | 生まれる → 生れる | 押さえる → 押える | 捕らえる → 捕える |

| 晴れやかだ → 晴やかだ | 聞こえる → 聞える | 積もる → 積る | 起こる → 起る |

| 落とす → 落す | 暮らす → 暮す | 当たる → 当る | 終わる → 終る |

| 変わる → 変る |

Note: The following words are deemed to follow Rule 1 instead: 明るい・荒い・悔しい・恋しい.

Excluding words dealt with via Rule 4, nouns shouldn’t have 送り仮名.

| 月 | 鳥 | 花 | 山 | 男 | 女 | 彼 | 何 | 草 | 上 | 下 |

Irregularities

1.

| 辺り | 哀れ | 勢い | 幾ら | 後ろ | 傍ら | 幸い | 幸せ | 全て | 互い | 便り | 半ば |

| 半ば | 情け | 斜め | 独り | 誉れ | 自ら | 幸い |

2. With the counter つ: 一つ, 二つ, 三つ, 四つ, 五つ, 六つ, 七つ, 八つ, 九つ, 幾つ

Nouns that come from a conjugatable part of speech or those made with the suffixes ~さ, ~み, or ~げ abide by the 送り仮名 spellings of the base word.

| 動き | 仰せ | 恐れ | 薫り | 香り | 曇り | 調べ | 届け | 願い | 晴れ | 当たり | 代わり | 向かい | 狩り |

| 泳ぎ | 答え | 祭り | 群れ | 憩い | 愁い | 極み | 初め | 近く | 遠く | 暑さ | 大きさ | 正しさ | 確かさ |

| 明るみ | 哀しみ | 憎しみ | 重み | 惜しげ | 可愛げ |

Irregularities

The following words do not have 送り仮名.

| 謡 | 虞 | 趣 | 氷 | 印 | 頂 | 帯 | 畳 | 卸 | 煙 |

| 謡 | 恋 | 次 | 隣 | 富 | 恥 | 話 | 光 | 舞 | 折 |

| 謡 | 組 | 肥 | 並 | 巻 | 割 | 掛 |

Note: 送り仮名is only lost when their verbal sense is lost. Ex. 話し VS 話, 氷り VS 氷.

許容: In the case when there is no worry of a word being misread, 送り仮名 may be dropped in the following fashion for the words below.

| 曇り → 曇 | 届け → 届 | 願い → 願 | 晴れ → 晴 | 当たり → 当り | 代わり → 代り | 狩り → 狩 |

| 向かい → 向い | 祭り → 祭 | 群れ → 群 | 憩い → 憩 | 答え → 答 | 問い → 問 |

The final mora in adverbs, attributes, and conjugations is usually 送り仮名.

| Adverbs | 必ず | 更に | 少し | 既に | 全く | 再び | 最も |

| Attributes | 来る | 去る | |||||

| Conjunctions | 及び | 且つ | 但し |

Irregularities

・With more 送り仮名:

| 明くる | 大いに | 直ちに | 並びに | 若しくは |

・With no 送り仮名: 又

Adverbs/Conjunctions from Verbs/Adjectives or + particles:

| 併せて 〔併せる〕 | 至って 〔至る〕 | 恐らく 〔恐れる〕 | 絶えず 〔絶える〕 | 例えば 〔例える〕 |

| 努めて 〔努める〕 | 辛うじて 〔辛い〕 | 少なくとも 〔少ない〕 | 互いに 〔互い | 必ずしも 〔必ず〕 |

In regards to compound words excluding those dealt with via Rule 7, 送り仮名 is determined by the individual components’ 音訓.

1. Examples of words that conjugate:

| 書き抜く | 流れ込む | 申し込む | 打ち合せる | 長引く | 若返る | 裏切る | 旅立つ | 聞苦しい |

| 薄暗い | 草深い | 心細い | 待遠しい | 軽々しい | 女々しい | 気軽だ | 望み薄だ |

2. Examples of words that do not conjugate:

| 石橋 | 竹馬 | 山津波 | 後ろ姿 | 斜め左 | 花便り | 独り言 | 卸商 | 水煙 | 目印 |

| 物知り | 落書き | 雨上がり | 墓参り | 日当たり | 夜明かし | 先駆け | 巣立ち | 手渡し | 入り江 |

| 合わせ鏡 | 封切り | 教え子 | 生き物 | 落ち葉 | 預かり金 | 寒空 | 深情け | 愚か者 | 行き帰り |

| 乗り降り | 抜け駆け | 田植え | 飛び火 | 伸び縮み | 作り笑い | 暮らし向き | 売り上げ | 取り扱い | 乗り換え |

| 引き換え | 歩み寄り | 申し込み | 移り変わり | 長生き | 早起き | 苦し紛れ | 大写し | 次々 | 常々 |

| 近々 | 深々 | 休み休み | 行く行く |

許容: When there is no worry of being misread, 送り仮名 can be dropped in the following fashion in the example words.

| 書き抜く → 書抜く | 申し込む → 申込む | 打ち合わせる → 打ち合せる・打合せる |

| 雨上がり → 雨上り | 申し込み → 申込み・申込 | 向かい合わせる → 向い合せる |

| 日当たり → 日当り | 引き換え → 引換え・引換 | 立ち居振る舞い → 立ち居振舞い・立ち居振舞・立居振舞 |

| 封切り → 封切 | 有り難み → 有難み | 呼び出し電話 → 呼出し電話・呼出電話 |

| 夜明かし → 夜明し | 暮らし向き → 暮し向き | 移り変わり → 移り変り |

| 入り江 → 入江 | 飛び火 → 飛火 | 合わせ鏡 → 合せ鏡 |

| 抜け駆け → 抜駆け | 待ち遠しい → 待遠しい | 売り上げ → 売上げ・売上 |

| 田植え → 田植 | 預かり金 → 預り金 | 取り扱い → 取扱い・取扱 |

| 落書き → 落書 | 聞き苦しい → 聞苦しい | 乗り換え → 乗換え・乗換 |

| 待ち遠しさ → 待遠しさ |

Note: In cases like こけら落とし, さび止め, 洗いざらし, 打ちひも whether either the front or end part of the word is written in かな instead of in漢字, you should not abbreviate 送り仮名 out.

Compounds may or may not have 送り仮名 according to convention.

1.The first in the guidelines with this rule are particular words of domain in which conventional spelling is recognized.

ア: Names of positions and titles:

| 関取 | 頭取 | 取締役 | 事務取扱 |

イ: Handicraft words that end in 「織」、「染」、「塗」、「彫」、「焼」等.

| 《博多》織 | 《型絵》染 | 《春慶》塗 | 《鎌倉》彫 | 《備前》焼 |

ウ; Others:

| 書留 | 気付 | 切手 | 消印 | 小包 | 振替 | 切符 | 踏切 | 手当 |

| 仲買 | 両替 | 割引 | 組合 | 売値 | 買値 | 倉敷料 | 作付面積 | 請負 |

| 借入《金》 | 小売《商》 | 取扱《所》 | 取扱《注意》 | 繰越《金》 | 乗換《駅》 | 取次《店》 | 取引《所》 | 乗組《員》 |

| 引受《人》 | 引換《券》 | 《代金》引換 | 引受《時刻》 | 振出《人》 | 待合室 | 見積《書》 | 売上《高》 | 貸付《金》 |

| 申込《書》 |

2. Spellings that are generally conventional.

| 奥書 | 木立 | 子守 | 献立 | 座敷 | 試合 | 字引 | 場合 | 羽織 | 葉巻 | 番組 | 番付 | 日付 |

| 水引 | 物置 | 物語 | 役割 | 屋敷 | 夕立 | 割合 | 合図 | 合間 | 植木 | 置物 | 織物 | 貸家 |

| 敷石 | 立場 | 建物 | 並木 | 巻紙 | 浮世絵 | 絵巻物 | 仕立屋 |

Notes:

1. Even when the items in 《》 are different, these guidelines still apply.

2. This list is not exhaustive. Therefore, as far as convention may be recognized, similar words are to be dealt with likewise. When it is hard to determine whether Rule 7 should be applied or not, use Rule 6.

Words specifically mentioned in the Cabinet guidelines from words within the bounds of the 常用漢字表, which includes not only lists of general characters but general readings with exceptions.

浮つく The reasoning for this is that the verb comes from the use of a suffix, つく.

お巡りさん This spelling is motivated by convention.

差し支える 立ち退く

Note: Alternatively, 送り仮名 within compound words such as this are often dropped. Thus, 差支える and 立退く. For compounds nouns, all 送り仮名 can be dropped. Ex. 話し合い・話合い・話合.

The following nouns were deemed to not ever have 送り仮名.

| 息吹 | 桟敷 | 時雨 | 築山 | 名残 | 雪崩 | 吹雪 | 迷子 | 行方 |

Yotsugana refers to the four Kana ジ, ヂ, ズ, and ヅ. More strictly speaking, however, it refers to these characters' distinctive pronunciations in Kyoto during the Heian Period. In Modern Japanese, though, how these four are pronounced and used is quite different depending on dialect, and modern spelling changes complicate matters. This lesson will try to take a deeper look into the issue so that you have full control over it.

Curriculum Note: This lesson uses IPA symbols.

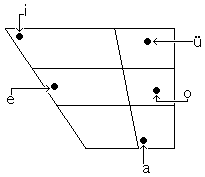

In Kyoto (京都) from the late 12th century to the early 14th century, the unvoiced sounds シ, チ, ス, ツ were pronounced as [ɕi] , [ti] , [su] , and [tu] respectively. ɕ is the Japanese sh sound, which is different in articulation than the English sh, and it has been pronounced as such for essentially all of Japanese's written history. However, the pronunciations of チ and ツ have not been so stable.

チ and ツ were plosives (sounds that stops all airflow), like the other t-sounds of Japanese, at the time. The voiced equivalents ジ, ヂ, ズ, and ヅ were respectively [ʑi] , [di] , [zu] , [du]. Today, the ʑ is the j-sound found inside words. The sounds シ, ジ, ス, and ズ were all fricatives (sounds that force air through a narrow channel). This was audible in Kyoto speech at the time, which is why the distinctions were shown in writing. Had any of these sounds been the same, we would possibly not have some Kana.

Problems with this analysis exist. There are words in which /z/ and /d/ have been interchangeable since the ancient period. This still happens in dialects today. For instance, some speakers of Japanese pronounce 全然 as "denden".

Examples of interchangeability in 四つ仮名 can be found in the word for whale. クジラ and クヂラ can both be found in the Kanchi'in Ruijumeigishō (観智院本『類聚名義抄』) Dictionary of 1251. Also during this time, people in the Kanto Region of Japan were mixing [zu] and [du] and [ji] and [di] in many words. It is believed that the spread of making these four sounds into two pairs of homophonous sounds started there. And, in the Tohoku Region, all four became homophonous to dzɯ̈.

From the early 14th century to the late 16th century, チ, ツ, ヂ, and ヅ became affricated (starting as a stop but releasing as a fricative). This made them [ʑi] ,[zu] , [ʥi] , and [ʣu] respectively, causing the differences between them narrower. From then on, people would mix up ジand ヂ and ズ and ヅ. So, although 水 was traditionally spelled as みづ, みず became more common. Likewise, 本寺 is supposed to be ほんじ, but ほんぢ was also used. By the end of the 16th century in places like Niigata, pronunciations had already shifted to the Modern Tokyo pronunciations. However, in places like Kyushu far removed from where these sound changes were taking place, the traditional distinctions were maintained.

From the 17th century to the late 19th century, this trend continued to spread. By the end of the 17th century, ヂ /ʥi/ became ジ [ʑi] and ヅ /ʣu/ became ズ [zu] even in Kyoto. However, the current conditional sound changes seen in Modern Tokyo speech started to develop. The affricate pronunciations returned before ん. And, depending on dialect, the affricate pronunciations were used in the word initial position. So, words that traditionally started with [ʑi] were regularly being pronounced with [ʥi] instead.

Certainly by the end of the 17th century, the pronunciations in Tokyo had already become what they are today. So, today ジ = [ʑi], ヂ [ʥi] =, ズ = [zɯ], and ヅ = [dzɯ]. ɯ represents the Standard Japanese pronunciation of う, and [u], which is like the English u, is found in other dialects of Japanese. This will be reflected in the transcriptions throughout this lesson. So, take note of these small details.

Regional Note: Much of this history is centered around Kyoto. Remember that 四つ仮名 started to be confused in other parts of Japan far more quickly. These regions eventually influenced Kyoto speech to bring about the changes mentioned in this discussion. Once the current changes had developed in Niigata and Kyoto, they would then be transplanted into what would become 標準語. Later in this lesson, we will see the paths other dialects took.

How these sounds should be written is not easy because of dialectical variation. The first book to standardize 四つ仮名 spellings was the 1695 蜆 縮 涼 鼓 集 . The first four characters when read with their native readings are examples of 四つ仮名. 蜆 = 蜆 (kind of clam), 縮み = ちぢみ (shrinkage), 涼み = すずみ (cooling off), and 鼓 = つづみ (hand drum). It proposed maintaining spelling differences, though only the elite and educated would care. What can be seen in the examples, however, is the still standing rule of when a sound is doubled but voiced, you use the 四つ仮名 variant for that sound. So, although 縮み is pronounced as チジミ, you still write it as チヂミ. Why? Well, that's the big question.

Fine, influential people want to maintain a system they've learned and propagated. However, it turns out that even literary geniuses such as 松尾芭蕉 didn't always spell things to standard. You can find him spelling 出づ, the classical form of 出る, as 出ず.

1. ついに

路

ふみたがえて石の巻といふ

湊

に出ず。

We ended up going the wrong way and entered a harbor called Ishinomaki.

In the Meiji Period, traditional orthography was maintained, but with the turn of the 20th century, 四つ仮名 spelling simplified to じ and ず respectfully, only allowing ぢ and づ used for 連濁 and agreement such as in つづく. However, you can find examples like つまづく (to stumble) being spelled as つまずく, ignoring etymological voicing altogether.

So, should students lose points for writing out 鼻血 as はなじ? I would because it's standardized as such, but does that mean the current system shouldn't be altered? There are two paths that could be taken to resolve the problem.

1. Align spellings to Modern Japanese pronunciation.

2. Revert back to the traditional spellings of 四つ仮名.

Either way, the spellings of many words would be changed, but they would be changed to spellings that have been used in the past and in some cases are still being used. Why should we care, though? Only those that like script reform and debates over orthography would probably care, but it's important to know as 四つ仮名 allows us to study Japanese pronunciation in more detail.

Though the exact pronunciation of 四つ仮名 fluctuates among Tokyo speakers, updates to the government's standard on this have been made as recently as 1986. Though the government's suggestions have no legal bearing on people, traditional distinctions such as 葛 (vine) being くず and 屑 (trash) being くづ have become abandoned. The same goes for 富士 (Fuji) and 藤 (wisteria), which were ふじ and ふぢ respectively.

Even so, we still have はなぢ, おこづかい (allowance), きづく (to notice), and つづく as exceptions, though the reason for why they are spelled that way is systematic and based on etymology. At one point, you could write a doubled voiced sound with ゞ (this character is an example of an 踊り字), but sadly this easy fix to the problem has not been used frequently since the end of the war. You still see it in the company name いすゞ, however. This spelling also happens to be easily accessible when typing.

So, what about cases such as つまづく・つまずく? つまづく is a clear combination of 爪 (nail) and the suffix -付く, but in the minds of speakers, the compound origin of this phrase has been lost to the point that both spellings are common. This may seem like a wishy-washy standard, but it is exactly how people decide whether both spellings are allowed for etymologically compound words in which ぢ and づ are produced.

However, what has caused great debate is the blatant ignoring of obvious compounding and using じ and ず anyway. The most egregious example is spelling the suffix ~中 as じゅう instead of ぢゅう. Another bad example is 稲妻 (lightning), clearly made of いな+ づま, being spelled as いなずま.

In Names

As you can imagine, if names can be read in so many different ways and spelled in so many different ways in 漢字, 四つ仮名 in names is rather random. For example, 千津子 is typically read as ちづこ, but some people read it as ちずこ. There isn't any pronunciation difference, and both readings can be used to type the name.

Changing the Spellings of the Readings of 漢字

Though to a degree, this is what's going on above, the most fundamental changes to Japanese script in regards to 四つ仮名 has been the fundamental altering of spellings to じ and ず that were historically ぢ or づ since being acquired from Chinese. For instance, 地 had the readings チ and ヂ, being acquired at different times. So, words like 地震 came into Japanese as ヂシン, not ジシン. Furthermore, the word is still pronounced as ヂシン. See the problem? The reason for changing the spelling is that the reading ヂ came in as such and was not a change due to 連濁.

Reality and the Ignoring of Dialectical Pronunciations

Of course, 地 is not the only example. 頭痛 should be づつう and 直に should be ぢきに, but that is just not how they're spelled anymore. This is despite the fact that there are still areas of Japan where 四つ仮名 distinctions are maintained. Even when writing out the dialects of these regions, it is not policy to distinguish them correctly in writing in favor of the standardized spellings.

| Word | Spell Change? | Original | New | Word | Spell Change? | Original | New |

| 泉 | Yes | いづみ | いずみ | 案じる | No | 案じる | 案じる |

| 味 | Yes | あぢ | あじ | 言伝て | No | ことづて | ことづて |

| 雫 | Yes | しづく | しずく | 埋める | Yes | うづめる | うずめる |

| 傷 | No | きず | きず | 築く | Yes | きづく | きずく |

| それじゃ | Yes | それぢゃ | それじゃ | ずつ | Yes | づつ | ずつ |

| ネズミ | No | ネズミ | ネズミ | 恥 | Yes | はぢ | はじ |

| 短い | No | みじかい | みじかい | 譲る | Yes | ゆづる | ゆずる |

| 水 | Yes | みづ | みず | 羊 | No | ひつじ | ひつじ |

| 虹 | No | にじ | にじ | つづら | No | つづら | つづら* |

| 沈む | Yes | しづむ | しずむ | 頷く | Yes/No | うなづく | うなづく・うなずく |

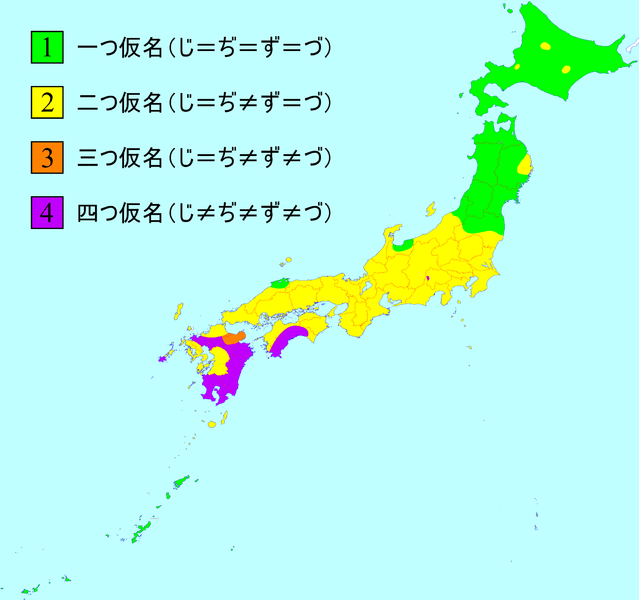

As has been discussed thus far, 四つ仮名 have been and continue to be pronounced differently in different dialects. As the picture above demonstrates, a dialect could fall under one of four categories in respect to 四つ仮名.

一つ仮名弁: Dialects in which じ = ぢ=ず=づ

二つ仮名弁: Dialects in which じ = ぢ≠ ず=づ

三つ仮名弁: Dialects in which じ = ぢ≠ ず≠ づ

四つ仮名弁: Dialects in which じ ≠ ぢ ≠ ず ≠ づ

標準語 is a 二つ仮名弁, just in case you didn't know. However, as we've seen, there are certain environments that allow for all four distinct pronunciations to be used. This categorization tells not how exactly they are pronounced but how they are used contrastively. In 四つ仮名弁, these sounds are all used to contrast words. So, the main focus in this section will be to study how exactly 四つ仮名 are pronounced in various dialects of Japanese.

一つ仮名弁

In 一つ仮名弁, there are two ways of saying them all based on specific dialect. If you are a speaker of Kita-ou'u Dialect (far north in Tohoku) or Unpaku Dialect (in Izumo), you pronounce them all as [ʣï]. The vowel is in between い and う as the two vowels merged in this region. If you are a speaker of Minami-ou'u Dialect, you pronounce them all as [ʣɯ̈]. Because of this, these dialects have been given the stereotypical name ズーズー弁.

四つ仮名弁

The completely opposite of 一つ仮名弁 are 四つ仮名弁. However, even though a dialect may have all four as separate sounds, these separate sounds are not uniformly the same throughout these dialects. Many parts of Kyushu, Kouchi Prefecture (高知県), the south of Nara Prefecture (奈良県南部), and Narada in Yamanashi Prefecture (山梨県奈良田) are all areas with 四つ仮名弁.

In 高知県, dialects may have the following pronunciations: ジ = [ʑi], ズ = [zu], ヂ = [di] ~ [dzi], ヅ= [du] ~ [dzu]. In Kagoshima Dialect (鹿児島弁), ジ =[ʑi], ズ = [zu], ヂ = [ʥi], and ヅ = [ʣu].

The Oddity of Narada Dialect in Yamanashi Prefecture

Narada is strength with its unique pronunciations: ジ = [ði], ズ = [ðu/dzu/zu], ヂ = [ɖʐi], ヅ = [ɖu/du]. It is also important to note that ツ = [tu] in this dialect. The ð is in English words like "that". These speakers would at least have less difficulty in one sound in English than other Japanese speakers. However, these speakers are dwindling very quickly as many are converting their speech to 標準語 standards.

Narata Dialect is first transitioning into a 三つ仮名弁 with most speakers not distinguishing じ and ぢ, though they may still not be exactly like in Standard Japanese. For the most part, the pronunciation reflects traditional orthography, but there are some words in Narada Dialect in which the sounds have flipped. So, for instance 葛 = 屑 as くず. Although 渦 was うづ, it is rendered as うず, which means it is either pronounced as [uzu], [udzu], or [uðu].

Research Note: To hear sound files of Narada Dialect for this information, see http://home.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/ikonishi/narada/narada_tu&du.html.

三つ仮名弁

三つ仮名弁 are not that common, but some speakers may naturally pronounce 四つ仮名 in this way at times regardless of dialect. Anyway, in these dialects such as 大分弁, ジ = ヂ, butズ doesn't sound like ヅ, which are [zu] and [dzu] respectively.

二つ仮名弁

As was said before, there is variation even among 二つ仮名弁. In 京都弁 where the allophonous (varying in specific environments) pronunciation rules developed, most speakers now lightly affricate all these sounds except AFTER ん. In recent years due to the contact of peoples from different parts of the country, and because script reform has gotten rid of the need to notice any traditional differences in pronunciation, most dialects are becoming 二つ仮名弁.

Transcription Note: Symbols in IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) are used in this lesson to make transcription as accurate and easy as possible. To look up glyphs that you don't understand, simply copy and paste the problematic ones into Wikipedia where you can find audio tapes for them.

In Classical Japanese works there are many かな that may seem very odd to the novice beginner. These かな are called 変体仮名. No, not へんたい as in 変態 but as in 変体.

変体仮名 are simply historical variants of the now standard ひらがな today. So, each mora had several possible ひらがな. The problem was not so in カタカナ as variants were made obsolete early in its development. 変体仮名 came from 万葉仮名, and many 変体仮名 originated from different 漢字.

変体仮名 were made obsolete in 1900 as one of the final reforms of the Meiji Reformation ( 明治維新). However, they still play a role in calligraphy, billboards, and authentic copies or replications of Classical works. 変体仮名 is also referred to as 異体仮名, making it clear that they can still be viewed as variants used at the author's will. It must be known, though, that not a lot of people know how to read them.

変体仮名 have played a very important role in writing ever since conception. People of the arts could liberally chose to their heart's desire what かな they wished to use, a continuation of the privilege people had when Japanese was still written in 万葉仮名.

変体仮名 are for the most part somewhat evolved forms of 万葉仮名 cursive style characters, from which other standard ひらがな derive from as well. As many 漢字 share the same 音読み, 変体仮名 inevitable came from a lot of characters, and many were made to represent the same sound.

変体仮名 are still seldom used. Many soba restaurant signs remind people of the character's glory-days and martial art centers and centers devoted to the preservation of historical events display them. Expect to see these characters by just going to a battlefield marker.

変体仮名 are not able to be viewed on computers. However, we will study by looking at the characters from this table from http://www10.plala.or.jp/koin/koinhentaigana.html

| 読み | あ | あ | あ | あ | あ | あ・を | い | い | い | い |

| 変 体 仮 名 |

||||||||||

| 字母 | 阿 | 安 | 安 | 愛 | 愛 | 悪 | 以 | 意 | 伊 | 移 |

| い | う | う | う | う | う | う | う | う・は | う | え |

| 異 | 宇 | 宇 | 有 | 有 | 雲 | 右 | 憂 | 羽 | 鵜 | 江 |

| え | え | え | え | え | え | お | お | お | か | か |

| 盈 | 盈 | 衣 | 要 | 得 | 縁 | 於 | 於 | 於 | 可 | 可 |

| か | か | か | か | か | か | か | か | か | か | か |

| 可 | 加 | 嘉 | 嘉 | 閑 | 賀 | 駕 | 我 | 家 | 香 | 佳 |

| が | が | が | が | が | が | が | が | が | が | が |

| が | が | き | き | き | き | き | き | き | き・こ | き |

| 起 | 幾 | 幾 | 喜 | 支 | 木 | 貴 | 期 | 記 | ||

| き | ぎ | ぎ | ぎ | ぎ | ぎ | ぎ | ぎ | ぎ・ご | ぎ | ぎ |

| 季 | ||||||||||

| く | く | く | く | く | く | ぐ | ぐ | ぐ | ぐ | ぐ |

| 具 | 久 | 九 | 求 | 供 | 倶 | |||||

| ぐ | け | け・と | け | け | け | け | け | け | け | げ |

| 希 | 計・斗 | 計 | 介 | 介 | 遣 | 気 | 気 | 稀 | ||

| げ・ど | げ | げ | げ | げ | げ | げ | げ | こ | こ | こ |

| 古 | 故 | 許 | ||||||||

| こ | こ | こ・ね | こ | こ・き | ご | ご | ご | ご | ご | ご |

| 許 | 胡 | 子 | 興 | 期 | ||||||

| ご | ご・ぎ | さ | さ | さ | さ | さ | さ | さ | さ | さ |

| 左 | 佐 | 佐 | 散 | 散 | 斜 | 乍 | 沙 | 狭 | ||

| さ | ざ | ざ | ざ | ざ | ざ | ざ | ざ | ざ | ざ | ざ |

| 差 | ||||||||||

| し | し | し | し | し | し | し | し | じ | じ | じ |

| 志 | 之 | 之 | 新 | 四 | 斯 | 事 | 師 | |||

| じ | じ | じ | じ | じ | す | す | す | す | す | す |

| 春 | 春 | 須 | 寿 | 寿 | 数 | |||||

| す | す | ず | ず | ず | ず | ず | ず | ず | ず | せ |

| 数 | 受 | 勢 | ||||||||

| せ | せ | せ | せ | ぜ | ぜ | ぜ | ぜ | ぜ | そ | そ |

| 世 | 世 | 声 | 瀬 | 楚 | 曽 | |||||

| そ | そ | そ | そ | そ | そ | そ | ぞ | ぞ | ぞ | ぞ |

| 曽 | 曽 | 所 | 所 | 処 | 処 | 蘇 | ||||

| ぞ | ぞ | ぞ | ぞ | ぞ | た | た | た | た | た | た |

| 多 | 多 | 多 | 堂 | 堂 | 田 | |||||

| た | だ | だ | だ | だ | だ | だ | だ | ち | ち | ち |

| 当 | 知 | 知 | 千 | |||||||

| ち | ち | ち | ち | ち | ぢ | ぢ | ぢ | ぢ | ぢ | ぢ |

| 遅 | 地 | 致 | 馳 | 智 | ||||||

| ぢ | ぢ | つ | つ | つ | つ | つ | つ | つ | づ | づ |

| 徒 | 徒 | 川 | 川 | 津 | 都 | 頭 | ||||

| づ | づ | づ | づ | づ | て | て | て | て | て | て |

| 天 | 天 | 亭 | 帝 | 帝 | 伝 | |||||

| て | て | て | で | で | で | で | で | で | で | で |

| 転 | 氐 | 低 | ||||||||

| で | と | と | と | と | と | と | と・け | ど | ど | ど |

| 登 | 登 | 東 | 度 | 砥 | 土 | 斗・計 | ||||

| ど | ど | ど | ど・げ | な | な | な | な | な | な | な |

| 奈 | 奈 | 奈 | 那 | 那 | 那 | 難 | ||||

| な | な | な | に | に | に | に | に | に | に | に |

| 名 | 南 | 菜 | 爾 | 爾 | 丹 | 耳 | 仁 | 児 | 而 | 尼 |

| ぬ | ぬ | ぬ | ね | ね | ね | ね | ね | ね | ね | ね |

| 怒 | 努 | 駑 | 禰 | 禰 | 年 | 年 | 根 | 熱 | 音 | 寝 |

| ね | ね・こ | の | の | の | の | の | の | の | の | の |

| 念 | 子 | 能 | 能 | 能 | 野 | 乃 | 迺 | 農 | 農 | 濃 |

| は | は | は | は | は | は | は | は | は | は | は |

| 者 | 者 | 者 | 葉 | 葉 | 盤 | 盤 | 盤 | 八 | 波 | 婆 |

| は | は | は | は | は・う | ば | ば | ば | ば | ば | ば |

| 婆 | 半 | 破 | 芳 | 羽 | ||||||

| ば | ば | ば | ば | ば | ば | ば | ば | ば | ば | ぱ |

| ぱ | ぱ | ぱ | ぱ | ぱ | ぱ | ぱ | ぱ | ぱ | ぱ | ぱ |

| ぱ | ぱ | ぱ | ぱ | ひ | ひ | ひ | ひ | ひ | ひ | ひ |

| 飛 | 飛 | 悲 | 悲 | 比 | 非 | 日 | ||||

| ひ | び | び | び | び | び | び | び | び | ぴ | ぴ |

| 妣 | ||||||||||

| ぴ | ぴ | ぴ | ぴ | ぴ | ぴ | ふ | ふ | ふ | ぶ | ぶ |

| 婦 | 布 | 不 | ||||||||

| ぶ | ぷ | ぷ | ぷ | へ | へ | へ | へ | へ | へ | へ |

| 遍 | 弊 | 弊 | 辺 | 辺 | 倍 | 幣 | ||||

| へ | べ | べ | べ | べ | べ | べ | べ | べ | ぺ | ぺ |

| 変 | ||||||||||

| ぺ | ぺ | ぺ | ぺ | ぺ | ぺ | ほ | ほ | ほ | ほ | ほ |

| 保 | 保 | 保 | 本 | 本 | ||||||

| ほ | ほ | ほ | ぼ | ぼ | ぼ | ぼ | ぼ | ぼ | ぼ | ぼ |

| 報 | 奉 | 穂 | ||||||||

| ぽ | ぽ | ぽ | ぽ | ぽ | ぽ | ぽ | ぽ | ま | ま | ま |

| 満 | 満 | 万 | ||||||||

| ま | ま | ま | ま | ま | ま・め | ま | ま | み | み | み |

| 万 | 万 | 末 | 末 | 麻 | 馬 | 真 | 間 | 美 | 美 | 美 |

| み | み | み | み | む | む | む | む | む・も・ん | む・も・ん | む・も・ん |

| 見 | 三 | 微 | 身 | 無 | 舞 | 舞 | 牟 | 无 | 无 | 无 |

| め | め | め・ま | も | も | も | も | も | も | も | も・む・ん |

| 免 | 面 | 馬 | 毛 | 毛 | 毛 | 茂 | 茂 | 裳 | 母 | 无 |

| も・む・ん | も・む・ん | や | や | や・よ | や | や | ゆ | ゆ | ゆ | ゆ |

| 无 | 无 | 屋 | 也 | 夜 | 耶 | 哉 | 由 | 由 | 遊 | 遊 |

| ゆ | ゆ | よ | よ | よ | よ | よ | よ | よ・や | ら | ら |

| 遊 | 游 | 与 | 与 | 与 | 代 | 余 | 余 | 夜 | 羅 | 良 |

| ら | ら | り | り | り | り | り | り | り | り | る |

| 良 | 良 | 里 | 利 | 利 | 利 | 利 | 理 | 李 | 梨 | 留 |

| る | る | る | る | る | れ | れ | れ | れ | れ | れ |

| 留 | 累 | 流 | 類 | 類 | 連 | 礼 | 礼 | 礼 | 礼 | 麗 |

| ろ | ろ | ろ | ろ | ろ | ろ | ろ | わ | わ | わ | わ |

| 路 | 呂 | 呂 | 楼 | 露 | 婁 | 侶 | 王 | 和 | 和 | 倭 |

| ゐ | ゐ |

ゐ |

ゐ |

ゐ |

ゐ | ゑ |

ゑ |

ゑ |

ゑ |

を |

| 井 | 為 | 為 | 遺 | 委 | 衛 | 衛 | 衛 | 恵 | 恵 | 越 |

| を | を | を | を | を | を・あ | ん・む・も | ん・む・も | ん・む・も | ||

| > | > | |||||||||

| 遠 | 遠 | 乎 | 乎 | 緒 | 悪 | 无 | 无 | 无 |

Try learning 5 a day once you reach IMABI IV and you will be fine. Also, if you are interested in learning the cursive form of characters, this will also greatly lessen the stress of learning another writing system.

One thing that is important to know and that can greatly help you memorize 変体仮名 is to recognize where they originated. The following chart shows where all かな have derived from. The abbreviations 平, 片, and 変 will stand for ひらがな, カタカナ, and 変体仮名 respectively.

Reading names is extremely difficult. Personal names, surnames, and place names are all very difficult for learners of Japanese and Japanese natives to know how to read properly. Though a lifetime of experience in the language makes the process easier, there is not a foolproof way of being 100% certain 100% of the time. Despite this difficulty, this lesson will attempt to explain various aspects you can find in the readings of names.

Names, though, are truly important to people. The famous author known by the name of 森鷗外 upon his death gave the following statement in his will: 余ハ石見人森林太郎トシテ死セント欲ス。墓ハ森林太郎ノ外一字モホルベカラズ (I wish to die as Iwamijin Mori Rintarou. Do not carve any other letters other than Mori Rintarou on my grave. He was a native of Iwami, a part of present day Chiba Prefecture. His given name was 森林太郎, and he wished to die that way. In Japanese culture a lot of thought is put into a name. Think of this as you learn more about names.

Though there have been many characters used in name in both Chinese and Japanese for a very long time, in attempts to practically narrow down the number of characters and readings that could be used in names, a list of characters not already in the list of general use characters was created by National Language Committee in 1951. Although it has been updated several times since, it is enforced by the Ministry of Justice.

People can only have the 2136 常用漢字, 861 人名用漢字, and かな in their names. Any character outside of this is considered as a 表外字. Additions to the list are being considered in accordance to requests from parents. The increase of name characters is being done in attempts to increase the list of general use characters. In fact, in 2010 121 characters from the 人名用漢字表 were put into the 常用漢字表. This trend will probably continue as the use of 漢字 is re-surging due to typing technology and people's cultural pride in the use of 漢字 becomes ever stronger.

| 丑 | 丞 | 乃 | 之 | 乎 | 也 | 云 | 亘・亙 | 些 | 亦 |

| 亥 | 亨 | 亮 | 仔 | 伊 | 伍 | 伽 | 佃 | 佑 | 伶 |

| 侃 | 侑 | 俄 | 俠 | 俣 | 俐 | 倭 | 俱 | 倦 | 倖 |

| 偲 | 傭 | 儲 | 允 | 兎 | 兜 | 其 | 冴 | 凌 | 凜・凛 |

| 凧 | 凪 | 凰 | 凱 | 函 | 劉 | 劫 | 勁 | 勺 | 勿 |

| 匁 | 匡 | 廿 | 卜 | 卯 | 卿 | 厨 | 厩 | 叉 | 叡 |

| 叢 | 叶 | 只 | 吾 | 吞 | 吻 | 哉 | 哨 | 啄 | 哩 |

| 喬 | 喧 | 喰 | 喋 | 嘩 | 嘉 | 嘗 | 噌 | 噂 | 圃 |

| 圭 | 坐 | 尭・堯 | 坦 | 埴 | 堰 | 堺 | 堵 | 塙 | 壕 |

| 壬 |

夷 | 奄 | 奎 | 套 | 娃 | 姪 | 姥 | 娩 | 嬉 |

| 孟 | 宏 | 宋 | 宕 | 宥 | 寅 | 寓 | 寵 | 尖 | 尤 |

| 屑 | 峨 | 峻 | 崚 | 嵯 | 嵩 | 嶺 | 巌・巖 | 已 | 巳 |

| 巴 | 巷 | 巽 | 帖 | 幌 | 幡 | 庄 | 庇 | 庚 | 庵 |

| 廟 | 廻 | 弘 | 弛 | 彗 | 彦 | 彪 | 彬 | 徠 | 忽 |

| 怜 | 恢 | 恰 | 恕 | 悌 | 惟 | 惚 | 悉 | 惇 | 惹 |

| 惺 | 惣 | 慧 | 憐 | 戊 | 或 | 戟 | 托 | 按 | 挺 |

| 挽 | 掬 | 捲 | 捷 | 捺 | 捧 | 掠 | 揃 | 摑 | 摺 |

| 撒 | 撰 | 撞 | 播 | 撫 | 擢 | 孜 | 敦 | 斐 | 斡 |

| 斧 | 斯 | 於 | 旭 | 昂 | 昊 | 昏 | 昌 | 昴 | 晏 |

| 晃・晄 | 晒 | 晋 | 晟 | 晦 | 晨 | 智 | 暉 | 暢 | 曙 |

| 曝 | 曳 | 朋 | 朔 | 杏 | 杖 | 杜 | 李 | 杭 | 杵 |

| 杷 | 枇 | 柑 | 柴 | 柘 | 柊 | 柏 | 柾 | 柚 | 桧・檜 |

| 栞 | 桔 | 桂 | 栖 | 桐 | 栗 | 梧 | 梓 | 梢 | 梛 |

| 梯 | 桶 | 梶 | 椛 | 梁 | 棲 | 椋 | 椀 | 楯 | 楚 |

| 楕 | 椿 | 楠 | 楓 | 椰 | 楢 | 楊 | 榎 | 樺 | 榊 |

| 榛 | 槙・槇 | 槍 | 槌 | 樫 | 槻 | 樟 | 樋 | 橘 | 樽 |

| 橙 | 檎 | 檀 | 櫂 | 櫛 | 櫓 | 欣 | 欽 | 歎 | 此 |

| 殆 | 毅 | 毘 | 毬 | 汀 | 汝 | 汐 | 汲 | 沌 | 沓 |

| 沫 | 洸 | 洲 | 洵 | 洛 | 浩 | 浬 | 淵 | 淳 | 渚・渚 |

| 淀 | 淋 | 渥 | 湘 | 湊 | 湛 | 溢 | 滉 | 溜 | 漱 |

| 漕 | 漣 | 澪 | 濡 | 瀕 | 灘 | 灸 | 灼 | 烏 | 焰 |

| 焚 | 煌 | 煤 | 煉 | 熙 | 燕 | 燎 | 燦 | 燭 | 燿 |

| 爾 | 牒 | 牟 | 牡 | 牽 | 犀 | 狼 | 猪・猪 | 獅 | 玖 |

| 珂 | 珈 | 珊 | 珀 | 玲 | 琢・琢 | 琉 | 瑛 | 琥 | 琶 |

| 琵 | 琳 | 瑚 | 瑞 | 瑶 | 瑳 | 瓜 | 瓢 | 甥 | 甫 |

| 畠 | 畢 | 疋 | 疏 | 皐 | 皓 | 眸 | 瞥 | 矩 | 砦 |

| 砥 | 砧 | 硯 | 碓 | 碗 | 碩 | 碧 | 磐 | 磯 | 祇 |

| 祢・禰 | 祐・祐 | 祷・禱 | 禄・祿 | 禎・禎 | 禽 | 禾 | 秦 | 秤 | 稀 |

| 稔 | 稟 | 稜 | 穣・穰 | 穹 | 穿 | 窄 | 窪 | 窺 | 竣 |

| 竪 | 竺 | 竿 | 笈 | 笹 | 笙 | 笠 | 筈 | 筑 | 箕 |

| 箔 | 篇 | 篠 | 簞 | 簾 | 籾 | 粥 | 粟 | 糊 | 紘 |

| 紗 | 紐 | 絃 | 紬 | 絆 | 絢 | 綺 | 綜 | 綴 | 緋 |

| 綾 | 綸 | 縞 | 徽 | 繫 | 繡 | 纂 | 纏 | 羚 | 翔 |

| 翠 | 耀 | 而 | 耶 | 耽 | 聡 | 肇 | 肋 | 肴 | 胤 |

| 胡 | 脩 | 腔 | 脹 | 膏 | 臥 | 舜 | 舵 | 芥 | 芹 |

| 芭 | 芙 | 芦 | 苑 | 茄 | 苔 | 苺 | 茅 | 茉 | 茸 |

| 茜 | 莞 | 荻 | 莫 | 莉 | 菅 | 菫 | 菖 | 萄 | 菩 |

| 萌・萠 | 萊 | 菱 | 葦 | 葵 | 萱 | 葺 | 萩 | 董 | 葡 |

| 蓑 | 蒔 | 蒐 | 蒼 | 蒲 | 蒙 | 蓉 | 蓮 | 蔭 | 蔣 |

| 蔦 | 蓬 | 蔓 | 蕎 | 蕨 | 蕉 | 蕃 | 蕪 | 薙 | 蕾 |

| 蕗 | 藁 | 薩 | 蘇 | 蘭 | 蝦 | 蝶 | 螺 | 蟬 | 蟹 |

| 蠟 | 衿 | 袈 | 袴 | 裡 | 裟 | 裳 | 襖 | 訊 | 訣 |

| 註 | 詢 | 詫 | 誼 | 諏 | 諄 | 諒 | 謂 | 諺 | 讃 |

| 豹 | 貰 | 賑 | 赳 | 跨 | 蹄 | 蹟 | 輔 | 輯 | 輿 |

| 轟 | 辰 | 辻 | 迂 | 迄 | 辿 | 迪 | 迦 | 這 | 逞 |

| 逗 | 逢 | 遥・遙 | 遁 | 遼 | 邑 | 祁 | 郁 | 鄭 | 酉 |

| 醇 | 醐 | 醍 | 醬 | 釉 | 釘 | 釧 | 銑 | 鋒 | 鋸 |

| 錘 | 錐 | 錆 | 錫 | 鍬 | 鎧 | 閃 | 閏 | 閤 | 阿 |

| 陀 | 隈 | 隼 | 雀 | 雁 | 雛 | 雫 | 霞 | 靖 | 鞄 |

| 鞍 | 鞘 | 鞠 | 鞭 | 頁 | 頌 | 頗 | 顚 | 颯 | 饗 |

| 馨 | 馴 | 馳 | 駕 | 駿 | 驍 | 魁 | 魯 | 鮎 | 鯉 |

| 鯛 | 鰯 | 鱒 | 鱗 | 鳩 | 鳶 | 鳳 | 鴨 | 鴻 | 鵜 |

| 鵬 | 鷗 | 鷲 | 鷺 | 鷹 | 麒 | 麟 | 麿 | 黎 | 黛 |

| 鼎 |

The following 常用漢字 have 旧字体 variants that are allowed in names.

| 亞 (亜) | 惡(悪) | 爲(為) | 逸(逸) | 榮(栄) | 衞(衛) | 謁(謁) | 圓(円) | 緣(縁) | 薗(園) | 應(応) |

| 櫻(桜) | 奧(奥) | 橫(横) | 溫(温) | 價(価) | 禍(禍) | 悔(悔) | 海(海) | 壞(壊) | 懷(懐) | 樂(楽) |

| 渴(渇) | 卷(巻) | 陷(陥) | 寬(寛) | 漢(漢) | 氣(気) |

祈(祈) | 器(器) | 僞(偽) | 戲(戯) | 虛(虚) |

| 峽(峡) | 狹(狭) | 響(響) | 曉(暁) | 勤(勤) | 謹(謹) | 駈(駆) | 勳(勲) | 薰(薫) | 惠(恵) | 揭(掲) |

| 鷄(鶏) | 藝(芸) | 擊(撃) | 縣(県) | 儉(倹) | 劍(剣) | 險(険) | 圈(圏) | 檢(検) | 顯(顕) | 驗(験) |

| 嚴(厳) | 廣(広) | 恆(恒) | 黃(黄) | 國(国) | 黑(黒) | 穀(穀) | 碎(砕) | 雜(雑) | 祉(祉) | 視(視) |

| 兒(児) | 濕(湿) | 實(実) | 社(社) | 者(者) | 煮(煮) | 壽(寿) | 收(収) | 臭(臭) | 從(従) | 澁(渋) |

| 獸(獣) | 縱(縦) | 祝(祝) | 暑(暑) | 署(署) | 緖(緒) | 諸(諸) | 敍(叙) | 將(将) | 祥(祥) | 涉(渉) |

| 燒(焼) | 奬(奨) | 條(条) | 狀(状) | 乘(乗) | 淨(浄) | 剩(剰) | 疊(畳) | 孃(嬢) | 讓(譲) | 釀(醸) |

| 神(神) | 眞(真) | 寢(寝) | 愼(慎) | 盡(尽) | 粹(粋) | 醉(酔) | 穗(穂) | 瀨(瀬) | 齊(斉) | 靜(静) |

| 攝(摂) | 節(節) | 專(専) | 戰(戦) | 纖(繊) | 禪(禅) | 祖(祖) | 壯(壮) | 爭(争) | 莊(荘) | 搜(捜) |

| 巢(巣) | 曾(曽) | 裝(装) | 僧(僧) | 層(層) | 瘦(痩) | 騷(騒) | 增(増) | 憎(憎) | 藏(蔵) | 贈(贈) |

| 臟(臓) | 卽(即) | 帶(帯) | 滯(滞) | 瀧(滝) | 單(単) | 嘆(嘆) | 團(団) | 彈(弾) | 晝(昼) | 鑄(鋳) |

| 著(著) | 廳(庁) | 徵(徴) | 聽(聴) | 懲(懲) | 鎭(鎮) | 轉(転) | 傳(伝) | 都(都) | 嶋(島) | 燈(灯) |

| 盜(盗) | 稻(稲) | 德(徳) | 突(突) | 難(難) | 拜(拝) | 盃(杯) | 賣(売) | 梅(梅) | 髮(髪) | 拔(抜) |

| 繁(繁) | 晚(晩) | 卑(卑) | 祕(秘) | 碑(碑) | 賓(賓) | 敏(敏) | 冨(富) | 侮(侮) | 福(福) | 拂(払) |

| 佛(仏) | 勉(勉) | 步(歩) | 峯(峰) | 墨(墨) | 飜(翻) | 每(毎) | 萬(万) | 默(黙) | 埜(野) | 彌(弥) |

| 藥(薬) | 與(与) | 搖(揺) | 樣(様) | 謠(謡) | 來(来) | 賴(頼) | 覽(覧) | 欄(欄) | 龍(竜) | 虜(虜) |

| 凉(涼) | 綠(緑) | 淚(涙) | 壘(塁) | 類(類) | 禮(礼) |

The word 名乗り has several definitions, but before we hone in on the one to be the focus of this lesson, we'll begin by looking at its definitions from the fifth edition of the 広辞苑.

な-のり【名告・名乗】

①自分の名・素性などを告げること。また、その名。特に武士が戦場でおこなうもの。

To tell your name/lineage. Or, that name. Particularly what warriors do on the battlefield.

②売物の名を呼びあるくこと。

To walk around calling out one's things to sell.

③公家および武家の男子が、元服後に通称以外に加えた実名。通称藤吉郎に対して秀吉と名乗る類。

Real name aside from one's alias after attaining manhood for boys of the Imperial Court and military families. The sort seen with labeling oneself as Hideyoshi versus the alias Fujikichirou.

④漢字の、通常の読みとは別に、特に名前に用いる訓。

Kun readings used particularly in names aside from the normal readings of a Kanji.

⑤能や狂言の構成部分の一。登場人物が自己の身分や、そこに来た趣旨などを述べるせりふ。

A compositional part of Noh and Kyogen. Speech made by characters to tell one's status and intentions on coming.

名乗り in this lesson refers to meaning 4, which refers to special 訓読み in personal names and surnames. These readings are those that have been historically attributed to names and are well established readings that people have chosen for names for a long time.

Many names in Japanese, though, are made with just standard readings of characters. In fact, some of the most common surnames are as such.

| 鈴木 | すずき | 山田 | やまだ | 山本 | やまもと | 山口 | やまぐち | 川端 | かわばた |

| 夏目 | なつめ | 本田 | ほんだ | 澤田 | さわだ | 川崎 | かわさき | 杉本 | すぎもと |

| 加納 | かのう | 竹中 | たけなか | 石井 | いしい | 田口 | たぐち | 坂本 | さかもと |

| 大坪 | おおつぼ | 田村 | たむら | 片山 | かたやま | 辻本 | つじもと | 石田 | いしだ |

| 清水 | しみず | 細野 | ほその | 沼田 | ぬまた | 根本 | ねもと | 野呂 | のろ |

Spelling Note: Old characters such as 澤 instead of 沢 is common in names.

Reading Note: 清水, although an irregular reading, also happens to be a common word spelled this way. So, しみず will be treated as a standard reading.

Special readings can be used with other special readings or regular readings. There is no rule that a 名乗り reading must be used with another 名乗り reading. In fact, there is no standardization on the use of 名乗り. 名乗り will be in bold in the following examples.

| 飯田 | いいだ (Surname) | 新潟 | にいがた (Place name) | 圭輔 | けいすけ (Personal name) |

| 希 | のぞみ (Personal name) | 秀吉 | ひでよし (Personal name) | 英雄 | ひでお (Personal name) |

There is some concern as to how far one can use 名乗り and what should even be considered 名乗り. In Japan parents have complete liberty in how they wish for to read their child's name. However, the overwhelming majority of Japanese believe that parents should only give names to their children that the intended reading can be figured out. Attributing a reading that is not a standard reading or a 名乗り recognized in dictionaries (and most importantly the public) is not popular.

Names of Famous Literary Figures

| ペンネーム | 読み | 本名 | ペンネーム | 読み | 本名 |

| 二葉亭四迷 | ふたばてい しめい | 長谷川辰之助 | 森鷗外 | もり おうがい | 森林太郎 |

| 与謝野昌子 | よさの しょうこ | 与謝野志よう | 永井荷風 | ながい かふう | 永井壮吉 |

| 正宗白鳥 | まさむね はくちょう | 正宗忠夫 | 高浜虚子 | たかはま きょし | 高濱清 |

| 武者小路実篤 | むしゃのこうじ さねあつ | 々 | 平塚らいてう | ひらつか らいちょう | 奥村明 |

| 高村光太郎 | たかむら こうたろう | 高村光太郎 | 菊池寛 | きくち かん | 菊池寛 |

| 室生犀星 | むろう さいせい | 室生照道 | 佐藤湖鳴 | さとう ちょうめい | 佐藤春夫 |

| 金子光晴 | かねこ みつはる | 金子安和 | 尾崎士郎 | おざき しろう | 々 |

| 川端康成 | かわばた やすなり | 々 | 草野心平 | くさの しんぺい | 々 |

| 井上靖 | いのうえ やすし | 々 | 唐十郎 | から じゅうろう | 大鶴義英 |

| 樋口一葉 | ひぐち いちよう | 樋口夏子 | 国木田独歩 | くにきだ どっぽ | 国木田哲夫 |

| 夏目漱石 | なつめ そうせき | 夏目金之助 | 田山花袋 | たやま かたい | 田山録弥 |

| 長谷川時雨 | はせがわ しぐれ | 長谷川ヤス | 北原白秋 | きたはら はくしゅう | 北原隆吉 |

| 志賀直哉 | しが なおや | 々 | 斉藤茂吉 | さいとう もきち | 々 |

| 宇野浩二 | うの こうじ | 宇野格次郎 | 芥川龍之介 | あくたがわりゅうのすけ | 々 |

| 宇野千代 | うの ちよ | 々 | 山本周五郎 | やまもと しゅうごろう | 清水三十六 |

| 佐多稲子 | さた いねこ | 佐多イネ | 種田山頭火 | たねだ さんとうか | 種田正一 |

| 太宰治 | だざい おさむ | 津島修治 | 島崎藤村 | しまざき とうそん | 島崎春樹 |

| 三島由紀夫 | みしま ゆきお | 平岡公威 | 大田翔子 | おおだ しょうこ | 々 |

| 吉行淳之介 | よしゆき じゅんのすけ | 々 | 寺山修司 | てらやま しゅうじ | 々 |

| 泉鏡花 | いずみ きょうか | 泉鏡太郎 | 石川啄木 | いしかわ たくぼく | 石川一 |

| 野上弥生 | のがみ やえこ | 野上ヤヱ | 中里介山 | なかざと かいざん | 中里弥之介 |

| 宮本百合子 | みやもと ゆりこ | 宮本ユリ | 萩原朔太郎 | はぎわら さくたろう | 々 |

| 山本有三 | やまもと ゆうぞう | 山本勇造 | 横光利一 | よこみつ りいち | 横光利一 |

| 梶井基次郎 | かじい もとじろう | 々 | 小林多喜二 | こばやし たきじ | 々 |

| 堀辰雄 | ほり たつお | 々 | 坂口安吾 | さかぐち あんご | 坂口炳五 |

| 中原中也 | なかはら ちゅうや | 々 | 壺井栄 | つぼい さかえ | 々 |

| 火野葦平 | ひの あしへい | 玉井勝則 | 椎名麟三 | しいな りんぞう | 大坪昇 |

| 大岡昇平 | おおおか しょうへい | 々 | 島尾敏雄 | しまお としお | 々 |

| 柳田國男 | やなぎた くにお | 々 | 三木露風 | みき ろふう | 三木操 |

| 有島武郎 | ありしま たけお | 々 | 葛西善蔵 | かさい ぜんぞう | 々 |

| 広津和郎 | ひろつ かずろう | 々 | 原民喜 | はら たみき | 々 |

Reading Notes:

1. 志よう = しょう

2. 壮吉 = そうきち

3. 奥村明 = おくむら はる

4. 高村’s real name is read as たかむら みつたろう.

5. 菊池’s real name is read as きくち ひろし.

6. 清水三十六 is read as しみず さとむ.

7. 君威 = きみたけ

8. 石川一 = いしかわ はじめ.

9. 横光利一’s real name is read as よこみつ としかず.

10. 三木操 = みき みさお.

Even though you may never read even one novel of all of these literary figures, at least knowing how to correctly read their names will impress natives as you will inevitably encounter their names being invoked for whatever reason.

Using Rare 名乗り

Using rare 名乗り that still appear in dictionaries may cause problems as well. Consider the character 和, which has the 名乗り reading とし. Even so, it is usually read as わ or かず in names. If you were to name your male child the common name さとし but spell it as 佐和, people may understandably mistakenly read it as the common female name read as さわ, which is normally spelled that way.

This is not to say that ambiguous reading of names isn't a problem, which is why it's so difficult to read the names of people you personally don't know correctly for the first time. Gender ambiguity in names has actually been used by people who change the reading of their name when they get a gender change, and people can also choose to leave the reading of their name ambiguous to have slightly more privacy in their identity.

きらきらネーム

However, there are names called きらきらネーム that are really flashy names with cute (and some would say bizarre readings). For instance, people have named children 光宙 with the reading ぴかちゅう. On this end of the spectrum, how to read the name is not necessarily that difficult. Yet, societal consequences for names such as this is highly debated. These names may also be called DQNネーム.

| 天響(てぃな) | 緑輝(さふぁいあ) | 火星(まあず) | 姫凛(ぷりん) | 七音(どれみ) | 月(あかり) |

| 希星(きらら) | 陽(ぴん) | 神生理(かおり) | 星影夢(ぽえむ) | 美々魅(みみみ) | 姫奈(ぴいな) |

| 園風(ぞふぃ) | 男(あだむ) | 束生夏(ばなな) | 晴日(はるひ) | 精飛愛(せぴあ) | 宝物(おうじ) |

Choosing what the final letter of a name is--止め字--is an important decision, and the decision is highly based on what the previous sound. A lot of parents decide the final character before thinking about the rest of the name they want to give to their child.

止め字 for Girl Names

| ア | 亜, 明, 愛, 阿, 有, 綾, 安 | 星愛 |

| イ | 衣, 依, 伊, 意 | 真衣, 優衣 |